Industrial plants generate their own alternative energy

If you want affordable energy, sometimes you just need to generate it yourself. But, as quickly as plants see the potential economic benefit of installing their own renewable energy supplies, they become disillusioned almost as fast by the red tape of government incentives and zoning requirements.

Household product manufacturer SC Johnson (SCJ, www.scjohnson.com), for example, met strong local opposition when it announced its desire to erect three 400-ft-tall wind turbines at its Waxdale manufacturing facility in Mount Pleasant, Wisconsin., as part of its ongoing commitment to provide renewable energy for the plant. The facility is its largest global manufacturing plant and covers the area of 36 football fields. Nearby residents expressed concerns about the potential noise, sun flicker, impact on property values, and endangerment of wildlife.

“Nearly 40% of our company’s worldwide electricity comes from renewable energy,” says Fisk Johnson, SCJ chairman and CEO. “Installing wind turbines at Waxdale is one of the many ways we are working to further reduce our environmental footprint.”

After escorting local officials to a wind farm in nearby Fond du Lac County, the company demonstrated wind turbine noise levels to quell any uncertainties about the volume. Measurements were about 20 decibels lower than the sound of a passing car on the paved road, and SCJ offered to install landscaping at the facility to make the wind turbines more aesthetically pleasing. All of this spurred approval of a conditional-use permit by the local board, allowing the manufacturer to go ahead with its plans to produce 8-10 million kWh, or 15% of its energy needs, with wind power. The company plans to generate 100% of its own energy at the facility, with 60% of that coming from renewable energy sources, including two co-generation plants, one of which creates renewable energy from landfill gases.

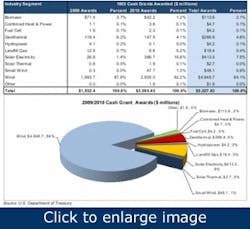

Alternative energy comes in many varieties — from biomass, landfill gas, and geothermal to solar, wind, and hydropower — but wind energy dominates not only the headlines and the skylines, but the federal grants for renewable energy projects (Figure 1). Wind and small-wind projects accounted for 85% of the U.S. Department of Treasury Section 1603 tax grants in 2009 and 2010.

Figure 1. Eighty-five percent of the U.S. Treasury Department’s Section 1603 tax grants were awarded to wind and small-wind projects in 2009 and 2010.

Wind turbines, of course, are capable of harnessing kinetic energy, turning it into mechanical energy and transforming that into electricity. The capital expenditure for wind turbines sometimes can deter the investment, but government incentives and grants can make that initial cost much more attractive. Plant managers or maintenance managers are typically the individuals who are best equipped to obtain that funding, but most don’t know where to begin.

The two most common federal incentives are the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA), which repealed the dollar cap on the small wind investment tax credit (ITC), enabling businesses to claim a 30% ITC for property with turbines used to generate its own power, and the Section 1603 tax grant program, which was extended in December. Add the various state and local incentives and grant programs, and you’ve got an overwhelming number of options to investigate, so where’s the best place to start?

Where to turn

Most plant managers have a relationship with either a local electrical contractor or electrical distributor for lighting, motors, or electrical components, explains Jeff Ehlers, president of Renewegy (www.renewegy.com). “I suggest starting with a local person that you trust and ask for that person’s guidance on wind power,” he suggests. “Most likely they have either been involved with a small wind project or know someone who has. There’s a lot of information on the Internet regarding small wind; however, it’s quite difficult to decipher. Like with any purchase, check references before you engage to be sure you have a good partner. Once you’ve decided who you might work with, ask for help in understanding wind power and the associated incentives.”

In 2011, Renewegy built a wind energy system that was tipped up at the North American headquarters of Wago (www.wago.us) in Germantown, Wisconsin. It included a 100-ft-tall, 32-ft-diameter windmill using portable hydraulics to raise and lower the unit in around 20 minutes (Figure 2). This will help to alleviate a considerable amount of the annual maintenance costs, which typically run about 5% of the installation cost. It’s the VP-20 wind turbine’s hydraulic tip-up capability, along with the internal CANbus communication, which is converted to Ethernet for remote monitoring, that differentiate it from other systems.

Figure 2. A portable hydraulic cylinder system can raise the turbine at installation and then lower it for servicing.

The VP-20’s tip-up capability is enabled by its monopole Tip-Down tower, which enables the portable hydraulic cylinder system to raise the turbine at installation and then lower it for servicing. This tip-up method eliminates the cost and time required by cranes and heavy-duty equipment used to install and help maintain larger wind turbine towers.

Other VP-20s have been installed at SCA Tissue in Neenah, Wisconsin, and at the North Texas Job Corp Center in McKinney, Texas. VP-20’s three blades are usually situated at a 10° pitch, but they can be turned to achieve as much as a 110° pitch to better handle variable wind speeds and improve power output. Its variable-pitch (VP) capability is patterned after utility-scale turbines, and it controls pitch for each blade to within 0.1° while pitching at speeds up to 15° per second. A closed-loop, Active-Pitch servo manages blade speeds in wind conditions of 6.7–55.9 mph, and an Active-Yaw servo ensures optimum power generation by directing the blades into the wind.

At 100 rpm, the turbine begins to produce power, and at 110 rpm it generates its normal 20 kW.

The complete system also includes power supplies, cables, connectors, fuse blocks and a backup capacitor module and can generate 20 kW of power, or up to 10% of the facility’s electricity demand. Estimated wind energy costs hover around $0.05/kWh, and the $80,000 price tag of the system was more than halved by energy incentives.

Pay it forward

[pullquote]Payback for a new wind-turbine installation typically is in the 5-15 year range, depending on manufacturer, wind resource, electricity costs, and incentives, explains Ehlers. “Remember that payback calculations generally assume the turbine is operational 100% of the time,” he cautions. “And remember that reliability and safety of the turbine system are as important as payback.”

Some grants, such as the federal 1603 incentive, are based on the total installed cost, says Ehlers. Some grants are based on the performance of the turbine in kilowatt hours. Some are a fixed dollar amount.

“Performance incentives are typically based on the kWh produced by the turbine in a year,” he explains. “An incentive of $1 to $2 per kWh generated might be a reasonable toward the cost of a project. For example, 20,000 kWh per year at $2/kWh equals $40,000. Most performance grants have a cap on the total dollar amount.”

Incentives can be grants, tax credits, or feed-in tariffs, which are very popular in Europe, says Ehlers. “They can be offered at the federal, state, and local levels,” he explains. “Utilities, non-profit foundations, municipalities, and private donors may also help fill gaps in funding for a wind power project. Feed-in tariffs result in shortening the payback on a project by paying higher than retail rates for electricity sold back to the grid. Such tariffs don’t help the up-front cost of the project, but help over the life of the project.”

Ehlers believes, regardless of subsidized funding, wind and solar power are here to stay. “Incentives provide a throttling mechanism to accelerate or decelerate its growth,” he admits. “If you ask 10 people about the value of renewable energy, you will most likely get 10 different answers, with some of them being quite emotional. Our country is in a state of transition with our source of energy. We all know we need to change course, but we don’t know exactly how or when.”

But Ehlers also believes renewable energy is not the only answer. “It will take an intelligent combination of investments in technologies formulated into a long-term strategic plan for our country,” he explains. “This is called an energy policy, and I think we all agree it’s time for our politicians to have a bipartisan debate and get on with our future. Wind and solar energy will slow down but not stop.”

Tower of power

In August 2011, Lincoln Electric (www.lincolnelectric.com) dedicated a newly erected 443-ft-tall wind tower at its world headquarters in Euclid, Ohio. The project was a global effort, with the can sections coming from Katana Summit (www.katana-summit.com) in Columbus, Nebraska, the polymer blades produced by LM Wind Power (www.lmwindpower.com) in Poland, and the turbine’s Synderdrive synergetic drive train made by Germany’s Kenersys (www.kenersys.com). The wind tower is comprised of 220 tons of steel and has the ability to generate 2.5 MW of electricity, or 10% of the Lincoln Electric campus’ needs.

The wind tower endeavor included Lincoln Electric’s first grant-righting effort. “The project’s underlying facts are what carried the grant to fruition,” says Seth Mason, maintenance manager at Lincoln Electric and the individual primarily responsible for obtaining the grant money.

The state of Ohio announced the State Energy Plan on June 26, 2009, giving organizations three months to submit their grant requests to the Ohio Department of Development, which was the administrator of U.S. Department of Energy funds that were available through ARRA.

The grant request required information, such as the name, qualifications and references of the contractor or installer, budget forms, financial documentation of funds availability, an interconnection agreement, and Section 106 historical review clearance. The grants were then awarded two months later on Nov. 30, 2009.

“The grant process was new to the state in regards to the ARRA funds, so for a couple of months the state was working with the U.S. Department of Energy to finalize details,” explains Mason. “The grant was in place prior to the purchase order placement for the wind turbine. Grants come with completion dates and these dates become fundamental to the development of the timeline.”