The Army uses a well-defined preventive maintenance process to maintain their equipment that includes a criticality assessment of the equipment to determine frequency and spare parts availability. Does your site have a defined list of assets with criticality ratings to determine PM/PdM requirements? How does your organization develop consistent training for the PMs? Does your program include QA/QC for continuous optimization?

Do you have an effective preventive maintenance program for your valuable equipment? How do you determine the effectiveness of your PM program? Have you ever considered how the United States Army preforms PMs on their equipment around the world using soldiers from all walks of life to operate and maintain equipment in top condition to accomplish their mission?

The Army uses a standardized system to develop PMs for all their equipment based on criticality. It includes:

- standards to measure the equipment readiness

- standardized training for those who perform the PMs

- manuals for operating and maintaining the equipment

- spare parts lists to improve maintainability and availability.

The military PM process as a model can help to improve industrial PM programs. This two-part article also will cover the process for reviewing existing PM programs along with case studies to illustrate the benefits of PM optimization. Finally, the importance of effective leadership (not just supervision) and its influence on program effectiveness will be covered briefly.

Why does an organization perform PMs? I have been in organizations that have limited or no PM in their maintenance processes. If PMs were performed, they were only done on some equipment—with no regard for equipment criticality—and were merely set up to justify headcount.

Why does the Army perform preventive maintenance? According to the Commanders’ Maintenance Handbook, “Preventive maintenance operations performed by soldiers in field organizations that preserve the operational condition and inherent reliability of equipment, comprise the most critical of all of the building blocks in the Army maintenance system” (DA PAM 750–1, page 2). In this one sentence, the Army is stating that the PM program is the most critical part of their maintenance system. This handbook is equivalent to an industrial site’s maintenance strategy or procedure on how to perform day-to-day maintenance activities, including preventive maintenance. Portions of this handbook could be used to develop the structure and framework for an organization’s maintenance and preventive maintenance operations.

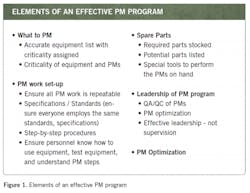

Why does the Army deem its PM program as the most critical part of their maintenance program? If military equipment fails, people can die, and they can fail in their mission to defend the country. Why do industrial organizations perform PMs? What is the goal in taking time out of the schedule to work on equipment that is still working? The intent of a PM program is to maintain equipment (keep if running) while looking for possible issues and to repair it before it fails, thereby avoiding unscheduled downtime. Another goal is to avoid introducing human error during the PM by using fit-for-purpose, repeatable PMs performed by qualified craftsmen (see Figure 1). Just as with the military, preventive maintenance should be the foundation of an organization’s maintenance operations, through which improved reliability, safety, and environmental performance is achieved.

Asset register with assigned criticality

How does the Army perform PMs? The first step of a good PM program is to determine what equipment you have and prioritize the equipment based on your mission or what you produce. Each unit in the Army has a Table of Organization and Equipment that lists the equipment the unit will have on hand to accomplish its mission. This is basically an asset register down to the lowest level of equipment for both maintainability and accountability. Furthermore, based on its missions, the unit will have an assigned criticality to each piece of equipment and its spare parts stock. Different units will have different criticalities for the same equipment based on their mission, but even within the unit, different criticalities may be assigned based on availability, which will determine the unit’s ability to be deployed and to complete its mission.

An asset register is also the first step for an industrial organization to set up, maintain, and optimize a PM program. Without an accurate list of equipment, an organization will never be able to have an effective PM program. Furthermore, this list must be down to the maintainable equipment level to track that equipment’s repair history and costs. Some organizations will have an asset register at a system level, but this method will be ineffective at isolating the actual failures within the loop.

Imagine if the Army’s asset register stopped at the system level, say, at the Apache Helicopter. All failures would be listed as a failure of the helicopter, and we would not be able to see what subsystem on the helicopter was failing so we could focus our repair efforts.

Don’t stop short on your register! You must develop an accurate asset register to the maintainable equipment level. A method I have used in the past is to use Piping and Instrument Diagrams (P&IDs) along with a field verification to ensure accuracy. From the P&IDs, list the equipment at the maintainable level of equipment. Next, use your criticality assessment process to assign a criticality and place this list into your Computerized Maintenance Management System (CMMS). Your criticality study will help you focus your personnel resources along with your spare parts to accomplish the mission of your organization.

Determine failure modes

You must also develop a PM strategy procedure that covers the overall development, operation, and strategy of your PM program. For the development of the PMs to address the identified failure modes of the equipment, I like to use the Failure sModes and Effects Analysis (FMEA, see Figure 2). For each piece of equipment, the failure modes are analyzed and then a list of PMs are developed to ensure the continued operational integrity of the equipment. We then review the PMs against the equipment’s actual operated conditions along with the experiences of the site personnel to develop the finalized list of PMs to perform on the equipment. The PMs should specify which equipment will have PMs performed by maintenance, operations, or by outside maintenance crews. No matter who performs the PMs, the personnel should be qualified to perform each task and to document all work done on the equipment. Not all equipment will have PMs performed on it based on the criticality and available resources, but as many PMs as possible should be performed by the daily user of the equipment or the operator.

Develop the technical manual

Once you have developed your asset register and list of PMs to perform, you will need to develop the PMs and the training for the personnel who perform them. To be effective, the PMs must be repeatable, be based on standards, have step-by-step instructions, and be performed by qualified and trained personnel using the correct test equipment. The Army uses an established and standardized process of performing PMs. Each piece of equipment has a technical manual that covers operating instructions, maintenance/PM instructions, components, reference, and supplies/material lists. Each of these components can be related to the industrial sector, as shown in Figure 3.

The technical manuals are generally uniform for all equipment, making it easy to use from one piece of equipment to the next. They provide all the material required to perform the equipment PMs with detailed information and performance measures for each step. This material can be used to develop training that is also based on tasks, conditions, and standards. I am not advocating that you develop a detailed technical manual for each piece of equipment, but you should have training based on task conditions and standards for each PM performed. You can gather information about the equipment from the OEM, along with your site procedures, to develop a process to organize information to assist in the development of PMs and training on the PMs.

Let’s look at an example of an Army Technical Manual using a piece of equipment that is carried by every soldier and is considered a critical piece of equipment: the personal gas mask. The manual has 15 pages on how to properly operate the mask, including pictures of each part of the mask (see Figure 4). Next there are 115 pages covering 46 Preventive Maintenance Checks and Services to be performed on the mask, including the interval, the task, and the standard to perform the task.

For other equipment, there may be levels of PMs that are performed by a higher-level maintenance worker, but it will have similar detail with respect to the task, conditions, and standards. This level of detail for each piece of equipment provides excellent information to develop training for the personnel performing the PMs. Such development of manuals and training result in consistency across separate locations in execution of the PMs.

The manual also provides:

- information or references to additional materials to support the maintenance and care of the specific equipment

- a list of components that are part of the equipment being maintained

- a spare parts list to maintain the equipment.

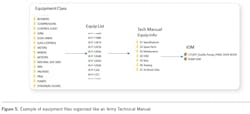

Translating this to past industrial sites, I have set up files for all the equipment, as shown below in Figure 5. This equipment class lists all our equipment at the site. Within each equipment class, we developed an equipment list, and for each piece of equipment, we organized files as shown in the Technical Manual. From this manual, we also developed training on the equipment and the PMs to be performed. This equipment was also linked to the equipment in the CMMS and could be accessed by personnel from a computer, tablet, or phone. The training for the maintenance was based on task, conditions, and standards and can be reviewed in a paper titled “How Your Plant Can Train Like the Military”.

Figure 5 provides a good example of how to organize your equipment information to provide not only how to perform preventive maintenance on the equipment, but also spare parts, general information, and detailed information that can be used for training and PM forms for that equipment.

Develop the training

The Army uses a phased approach to train personnel on each piece of equipment as follows:

- classroom (crawl)

- hands-on (walk)

- testing in classroom and field as applicable (jog)

- perform PMs on the job (run).

Military training uses a structured process that covers task, condition, and standards along with performance measures for each PM. Training is structured and consistent throughout the military (not including local Standard Operating Procedures or SOPs). PM training and certification allow seamless transfers from unit to unit. Some additional training is carried out for site-specific requirements, such as temperature, altitude, and local regulations. Such training enables the soldier to go from the street to service in six months (although some skills take longer). This provides a good model for industrial sites to use to develop both craft task training and PM training that is consistent and can be used at multiple sites.

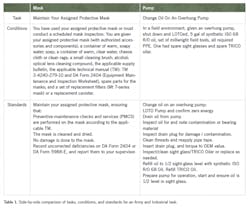

The classroom PM training would be set up using tasks, conditions, and standards. Table 1 shows a side-by-side comparison of tasks, conditions, and standards for the protective mask and a PM for changing oil on an over-hung pump.

Conclusion

The goal of this article is to provide the Army’s process of preventive maintenance as a guide for the industrial world. The Army’s structured PM process allows it to maintain its equipment across many regions of the world in both peace time and during combat operations. The process can be reviewed and adapted for any industrial site to set-up a new program or improve an existing program and is available for review on the Internet. Annex B provides an Army and Industry Comparison of Maintenance and Management Competencies and can be used to compare you current PM process to the Military’s.

Part 2 of this article continues next month, and includes coverage of PM optimization and leadership.

This story originally appeared in the June 2022 issue of Plant Services. Subscribe to Plant Services here.