You might have heard a lot of buzz about last year’s revision to OSHA’s electrical standard and how it incorporated the National Fire Protection Association’s NFPA 70E, Standard for Electrical Safety in the Workplace. That is not entirely the case.

OSHA revised its electrical standard, but it revised only one section, the Design Safety Standards for Electrical Systems (29 CFR 1910.302 through .308). It didn’t touch the Safety-Related Work Practices section (29 CFR 1910.331 through .335).

So, the bottom line is, nothing has changed regarding arc flash, working on deenergized electrical systems, working on live electrical components, lockout/tagout procedures or electrical personal protective equipment (PPE).

If you have been doing things correctly in the past, then this article will be a refresher. If you’re not sure you’re doing things right, this article might help you to get on track.

Lockout/tagout remains key

It really needs to be emphasized that when working on electrical systems, the required way to protect employees is electrical lockout/tagout (Figure 1). This requirement hasn’t changed. OSHA says in §1910.333(a)(1):

Live parts to which an employee may be exposed shall be deenergized before the employee works on or near them, unless the employer can demonstrate that deenergizing introduces additional or increased hazards or is infeasible due to equipment design or operational limitations. Live parts that operate at less than 50 volts to ground need not be deenergized if there will be no increased exposure to electrical burns or to explosion due to electric arcs.

Note 1: Examples of increased or additional hazards include interruption of life support equipment, deactivation of emergency alarm systems, shutdown of hazardous location ventilation equipment, or removal of illumination for an area.

Note 2: Examples of work that may be performed on or near energized circuit parts because of infeasibility due to equipment design or operational limitations include testing of electric circuits that can only be performed with the circuit energized and work on circuits that form an integral part of a continuous industrial process in a chemical plant that would otherwise need to be completely shut down in order to permit work on one circuit or piece of equipment.

OSHA hasn’t changed the requirement in 29 CFR §1910.333(a)(1) that says, “Live parts to which an employee might be exposed shall be deenergized before the employee works on or near them, unless the employer can demonstrate that deenergizing introduces additional or increased hazards or is infeasible because of equipment design or operational limitations.”

The NFPA 70E has a similar requirement, except that the term “electrically safe work condition” is used instead of “deenergized.” The 70E places this requirement, just as OSHA does, ahead of donning appropriate PPE and working on live electrical systems or components. Both documents provide specifics on how to achieve this deenergized state or electrically safe work condition using lockout/tagout procedures and devices.

Quite often, employers try to take advantage of the terms “operational limitations” and “continuous industrial process” to justify not locking out and tagging electrical systems before work is done. OSHA hasn’t addressed the terms and conditions for working on live electrical systems. However, a December 19, 2006 OSHA Letter of Interpretation, Continuous Industrial Processes and the Infeasibility of Deenergizing Equipment Under 29 CFR 1910.333, sheds some light on the issue. (You can read all the letters mentioned in this article on the OSHA Web site at www.osha.gov.)

Avoid working live

For electrical work, you don’t want your maintenance technicians to don PPE unless it’s absolutely necessary. Voltage-rated rubber gloves and leather protective gloves are unwieldy. It also can be difficult to work on electrical equipment with other PPE they might have to wear, such as face shields, flash suit hoods and jackets. The OSHA requirement at §1910.335(a)(1) says:

Employees working in areas where there are potential electrical hazards shall be provided with, and shall use, electrical protective equipment that is appropriate for the specific parts of the body to be protected and work to be performed.

This language doesn’t provide the specifics an employer needs to follow to protect technicians against electrical hazards.

OSHA also says in §1910.132(d) that employers must perform a hazard assessment and equipment selection, and document the hazard assessment. However, OSHA provides no help when determining what electrical PPE employees should wear. Fortunately, the NFPA 70E provides excellent help in determining specific hazards and appropriate PPE for electrical workers. (You can order the NFPA 70E on the National Fire Protection Association’s Web site.)

When using the 70E as the basis for working on or near live electrical components, there’s an important aspect you must consider: electric shock and arc flash/blast. The 70E discusses them individually and establishes the requirements for each hazard. Article 130.2 covers shock hazards and Article 130.3 covers arc flash hazards.

If your technicians work on live electrical components, the NFPA 70E is understandable and easy to use. It provides numerous ways you can ensure attaining a safe working environment:

- Require an energized electrical work permit before anyone works on live electrical systems/components.

- Provide instructions for doing a shock and flash hazard analysis and setting up approach boundaries.

- Include a simplified, two-category, flame-resistant (FR) clothing system if your plant has a large, diverse electrical system.

- Chart examples of protective clothing systems and typical characteristics.

Points on PPE

Using the NFPA 70E to establish shock and flash protection boundaries ensures a safe working environment for your electricians and other nearby employees. However, you still must determine if you are meeting other OSHA electrical requirements. Consider the following each time anyone works on or near live electrical equipment:

- Electrical PPE must be clearly marked and electrically tested in accordance with the schedules in §1910.137. Employers also must ensure the equipment is maintained in a safe and reliable condition.

- If there is a chance that protective equipment, such as rubber gloves, can be damaged during use, employees must protect the insulating material. An example of how to protect the rubber would be to wear leather gloves over the rubber gloves.

- Employees must wear nonconductive head protection when there’s a danger of head injury from electrical shock or burns because of contact with exposed, energized parts.

- Employees must wear eye and face protection when there’s a danger of injury from electric arcs or flashes or from flying objects resulting from an arc flash/blast.

Use insulated tools

OSHA requires employees to use insulated tools and handling equipment if the tools or equipment might contact energized parts. The requirements say:

- When working near exposed, energized conductors or circuit parts, you must use insulated tools and handling equipment if they might make contact with live components or wiring. You must protect the insulation if it’s subject to damage.

- Fuse-handling equipment must be used to remove or install fuses when fuse terminals are energized. The tool must be insulated for the circuit voltage.

In an OSHA Letter of Interpretation dated May 20, 1966, an employer inquired about the requirement for wearing rubber insulating gloves when using insulated hand tools. Is it a requirement? OSHA’s response was:

When working near exposed, energized electrical conductors or circuit parts, the OSHA standard does not specifically require that employees wear rubber insulating gloves when using insulated hand tools.

However, wearing rubber gloves when using an insulated hand tool may be appropriate for a particular work application. For example, if an employee’s hand is exposed to contact with energized parts other than the one being manipulated with the tool, rubber gloves would be required.

Respect test equipment

Using appropriate test equipment for the circuits being tested, and being familiar with the equipment, is critical. Many multimeters have been destroyed by inappropriate use, such as having the meter set on the wrong settings. An arc flash and subsequent injury can also occur from meter misuse.

According to an OSHA Letter of Interpretation dated June 22, 1998, you must ask the following questions to determine if rubber insulating gloves are needed when testing energized circuits:

- Are the probes designed so that the technician’s hand can slip off the end of the insulated handle?

- Are there other exposed, energized parts that the worker’s hand might contact during testing?

If probe designs don’t prohibit a hand from slipping off the end or there are other energized parts that might be contacted, OSHA says rubber insulating gloves are required.

If you answer yes to either question, OSHA says rubber insulating gloves or other electrical protective equipment is required (Figure 2).

Secure the work area

Two aspects of securing the work area and warning employees regarding electrical hazards are permanent markings and warning signs and barricading the area when live electrical work is in progress.

Electrical equipment, plugs, receptacles, circuit breakers and larger equipment must be marked so anyone can identify the manufacturer. OSHA regulations also require other markings giving voltage, current, wattage or other ratings as necessary.

“As necessary” usually means that equipment and equipment installations must be marked as required by the OSHA regulations and other industry standards. An example is the requirement in the National Electric Code (NEC) to “field” mark (the technician applies the label) certain equipment to warn qualified employees of potential arc flash/blast hazards. The warning is there specifically to remind qualified employees to wear appropriate PPE when working on equipment in an energized state. It also warns unqualified employees to stay away. (You can read the particulars regarding the label in the NEC at Article 110.16.) Other signs required by the OSHA regulations include:

600 volts, nominal, or less: Entrances to rooms and other guarded locations containing exposed live parts must be marked with conspicuous warning signs forbidding unqualified persons to enter.

More than 600 volts, nominal: Metal-enclosed switchgear, unit substations, transformers, pull boxes, connection boxes and other similar associated equipment must be marked with appropriate caution signs.

Entrances to buildings, rooms or enclosures containing exposed live parts or exposed conductors operating at more than 600 volts, nominal, must have permanent and conspicuous warning signs provided, substantially reading, “DANGER — HIGH VOLTAGE — KEEP OUT.”

Barricade and alert

When qualified employees work on live electrical components, the area surrounding the work zone must be effectively barricaded to prevent other employees from getting too close to the hazards. The NFPA 70E can be used to determine work boundaries. After the boundaries are established, both OSHA and the NFPA 70E suggest the following methods to keep unqualified employees safe:

- Safety signs, safety symbols or accident-prevention tags must be used where necessary to warn employees about electrical hazards. When placing signs and tags, the requirements at §1910.145, Specifications for Accident Prevention Signs and Tags, apply.

- Barricades must be used in conjunction with safety signs where it is necessary to prevent or limit employee access to work areas exposing employees to uninsulated energized conductors or circuit parts. Conductive barricades might not be used where they can cause an electrical contact hazard.

- Attendants: If signs and barricades don’t provide sufficient warning and protection from electrical hazards, an attendant must be stationed to warn and protect employees.

OSHA’s 29 CFR standard section §1910.334(a) requires a visual inspection of cords, plugs and receptacles before each shift for defects such as loose parts, damaged or worn insulation and deformed or missing prongs.

Check tools, cords and appliances

OSHA requirements for using portable electric (cord- and plug-connected) equipment are detailed in §1910.334(a). Section §1910.334(a) requires a visual inspection of cords, plugs and receptacles before using extension cords and portable equipment. The inspection is required before each shift where the equipment will be used. The requirements also say that defective equipment must not be used until replaced, repaired and tested.

Using equipment with defects, such as loose parts, deformed or missing prongs (Figure 3) and damaged or worn insulation on cords can cause injury and possible death.

There are no OSHA regulations or NEC requirements pertaining to personal fans, radios, heaters and other small appliances, and none prohibiting their use. However, OSHA addresses appliances in general. The bottom line regarding appliances in the workplace is:

- The equipment must be approved by an official approving agency such as Underwriters Laboratories (UL). Approved means the cord and appliance are tested together to ensure they’re matched as far as current-carrying and other capabilities. An equipment ground might or might not be required, depending on the conditions of use.

- The equipment must be used according to the manufacturer's installation and use requirements.

- The equipment must not be used in excess of its capabilities. If the equipment is marked “for household use only,” it must not be used in industrial applications. OSHA has stated in a Letter of Interpretation dated July 16, 2003 that “household use” does not limit the equipment for home use. The appliance could be used at work if it is used under the same conditions (i.e., being used in an office or break room).

Also, the OSHA requirements at §1910.303(b), Examination, Installation and Use of Equipment, apply. These regulations require that electrical equipment must be free from recognized hazards that are likely to cause death or serious physical harm to employees.

Adhere to intended purpose

At times, electrical equipment is installed or used in a manner for which it was not designed. The requirement at §1910.303(b)(2), Installation and Use of Electrical Equipment, is sometimes known as the General Duty Clause for Electrical Work. This is one of the electrical standards used by OSHA as a catchall for hazardous situations not covered by specific electrical standards. The application of the standard might be broad, but the intent is to ensure that all electrical equipment is installed and used as designed. The requirement says:

Listed or labeled equipment shall be installed and used in accordance with any instructions included in the listing or labeling.

In 2007, this requirement garnered more than 600 OSHA citations. One of OSHA’s most common applications of this standard is to address the situation where a multiple-receptacle box designed to be mounted on or in a wall is fitted with a power cord and placed on the floor to provide power for various tools. This is not a prescribed use for the receptacle box. Other electrical equipment misuses are:

- Using Romex wire for extension cords.

- Using outdoor equipment that is listed and labeled only for indoor dry locations. (This can even apply to double-insulated tools, which are listed and labeled for dry, indoor locations only.)

- Short, two-prong adapter plugs with a pigtail grounding connection to facilitate the attachment of cords and tools to electrical systems.

- Using the wrong size circuit breakers or fuses for overcurrent protection.

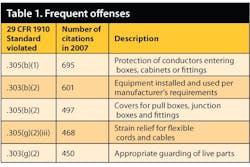

Other OSHA electrical standards frequently violated by employers in 2007 are in Table 1.

Follow best practices

Above all, lockout/tagout still rules. Both OSHA and the NFPA 70E require that you lockout and tag electrical equipment before working on it. Everyone agrees that you can’t get more protective than that. Only under certain conditions can you “keep the systems running” rather than deenergizing the equipment and rendering it electrically safe.

Although the NFPA 70E isn’t incorporated into the OSHA electrical standard by reference, OSHA recognizes the NFPA 70E as a best practice method to protect employees against electrical hazards. For this reason, OSHA can and has issued general-duty clause citations for hazards not covered in the OSHA regulations because the 70E provided a “best practice” method to eliminate the hazard.

Gerald Woodson is an editor at J. J. Keller & Associates Inc., Neenah, Wis. Contact him at (920) 727-7267 or [email protected].