Improve the reliability of your bin and silo flow

Bins and silos are a common sight at most industrial plants around the world. The smallest of these, such as hoppers used to feed tableting or briquetting presses, may contain only a few pounds of material. The largest include gigantic silos having capacities of tens of thousands of tons.

A common bin or silo function is providing surge capacity to smooth out process fluctuations, intermittent plant deliveries and production schedules. Sometimes these vessels are used to isolate batches or shipments from different suppliers; other times, they provide processing functions such as drying, heating, cooling or devolatilization.

The material stored in a bin or silo is generically referred to as a bulk solid. This term encompasses a wide range of materials varying in size from submicron powders to mine-run ores containing large boulders, and as chemically different as sugar, cocoa powder, limestone, coal, cement, sawdust, metal shavings and plastic pellets.

Reliability problems

Bin and silo reliability issues range from inability to discharge a bulk solid to difficulty controlling discharge rate, uniformity or quality of the discharging stream, as well as health and safety concerns:

No flow: Does the discharge from your bins sometimes simply stop? If so, you aren’t alone. This can be one of the most serious problems that a plant engineer or operator faces, because downstream operations may be starved to the point that a process line must be shut down. Having to shut down a reactor, melt furnace or kiln because of an upstream flow stoppage can be extremely costly.

Phenomena called aching and ratholing can interrupt bin discharge (Figures 1 and 2). An arch, which is a form of stable obstruction that can develop inside a storage vessel, is usually located at, or just above, the outlet. It occurs in this location because that is where the bin cross-section is narrowest. Mechanical interlocking of particles that are large relative to the size of the outlet or particles that bond together form the arch (Figure 3). In contrast, ratholing occurs when a stable, nearly vertical flow channel empties out and the material surrounding this channel remains stagnant.

Figure 1. Material can be so cohesive that only a limited active volume moves through the bin.

Figure 2. Ratholing leads to inefficient and uneconomical storage.

Erratic flow: Perhaps the bulk solid discharges, but its flow rate or bulk density varies widely. This, too, can be detrimental to safe, reliable plant operation. Flow aids such as sledgehammers, bin vibrators and air cannons often are used in attempts to keep bins free flowing, but these measures aren’t always effective or reliable.

Flow rate concerns: When handling fine powders, a bin’s discharge rate can be extremely high if the material fluidizes and floods uncontrollably through the hopper outlet like water through a faucet. When this occurs, the resulting spilled material is, at a minimum, a housekeeping headache and may have to be scrapped. The flooding material could pose an airborne health risk or may overwhelm downstream processes, necessitating a shutdown.

At the other end of the spectrum, the rate at which material discharges from a bin may be much lower than the downstream process requires. Simply increasing the feeder speed won’t correct this problem if the source is a flow rate limitation through the hopper outlet.

Segregation: Many bulk solids consist of a blend of particles of different sizes, densities or chemical compositions. If the particle stream discharging from the bin has significant variations in these properties, it can cause severe quality control problems. This problem is particularly acute in pharmaceutical plants that manufacture solid dosage forms, where the critical blend of expensive active drug and inactive excipients must be maintained within close tolerances down to virtually every tablet or capsule being produced.

Limited live capacity: Ratholing reduces the live or usable capacity of the vessel to the volume of the rathole, which can be as little as 10% to 20% of the nominal bin volume. A bin or silo in which ratholing occurs is an uneconomical storage vessel that needs to be refilled more frequently than necessary.

Product degradation: A bulk solid also can degrade over time while it’s stored in bins and silos, affecting its quality as well as ability to discharge. Examples include chemical powders and food products such as sugar that are prone to caking, food products that spoil if they sit too long without movement, and materials such as coal that oxidize, resulting in spontaneous combustion. These problems generally occur in bins and silos that exhibit a first in, last out flow sequence.

Health and safety concerns: Many workers experience back injuries each year from using sledgehammers to beat against the sides of bins and silos to coax the stored material to discharge. Attempts to restart flow may expose plant personnel to hazardous bulk solids; in some cases lives have been lost during attempts to unplug large silos. If flow does occur but is uncontrolled, it can generate excessive dust that might be hazardous to nearby workers or violate emission regulations. Also, such abused bins and silos experience an unacceptably high rate of structural problems including, sometimes, complete collapse of the structure with accompanying property damage and personal injury, even death.

How to improve reliability

The first step is to know the properties of the bulk solid in the bin. No one would think of designing a vessel to store water without knowing whether it’s going to be ice, liquid or steam. Yet it’s all too common for engineers who need to design bulk storage bins and silos for their plants to specify simply the generic name of the bulk solid to be stored, e.g. coal. Variations in particle size, chemical composition and other variables can alter the flow properties of a bulk solid dramatically. The result is that samples of similarly named materials can be, in terms of flowability, completely different.

Appropriate physical testing includes measurements of cohesive strength, internal and wall friction, compressibility, permeability, segregation characteristics and other variables. Many of these test procedures have been standardized by ASTM. You can use these well-developed test procedures and equipment to measure the flow characteristics of your bulk solids, or contract with a testing laboratory that specializes in this type of work.

The flow properties of a bulk solid typically vary with:

- Particle size distribution -- Generally smaller particle sizes or wider ranges of sizes make a bulk solid less flowable.

- Moisture content -- Higher moisture generally makes a bulk solid less flowable, until saturation is approached.

- Temperature -- Both absolute temperature as well as temperature changes can affect a bulk solid’s flow properties.

- Time in storage at rest – Typically, the longer a bulk solid sits without movement, the greater its cohesive strength and adhesion to surfaces.

Any tests run on your bulk solid should accurately duplicate the conditions of each of these variables as they occur in your plant. Otherwise, the test results may prove to be useless.

Design for flow

Once you’ve determined the flow properties of the bulk solid, you can use well-proven procedures and calculations to design retrofits for existing bins and silos that will better promote reliable discharge. You can use these same flow properties and procedures to design new vessels that will perform reliably.

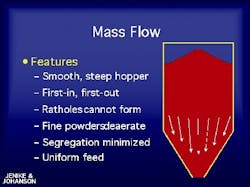

The first step is to determine the appropriate flow pattern -- mass flow or funnel flow. Mass flow is defined as a flow pattern in which all the material is in motion whenever any is withdrawn (Figure 4). This requires smooth, steep walls in the hopper or converging section. How smooth and how steep is determined by the flow property measurements.

Figure 4. All the material is in motion whenever any is withdrawn from the bin bottom.

Funnel flow bins, on the other hand, feature a stagnant zone of material along the hopper walls that extends into some portion of the volume at the top of the bin (Figure 5). Funnel flow bins are suitable for coarse, free flowing, non-degrading bulk solids where segregation is unimportant. If any one or more of these four characteristics don’t describe your material, use mass flow designs for your hopper.

Figure 5. This flow is suitable for coarse, free flowing, non-degrading bulk solids for which segregation is unimportant.

After selecting an appropriate flow pattern, design your vessel to prevent arching and ratholing, achieve the required discharge rate and minimize particle segregation. If you do the research, you’ll find the design procedures are well known. Alternatively, find a consulting engineering firm that specializes in providing this service.

Don’t forget the feeder: Discharge from most bins and silos is controlled by a feeder, such as a rotary valve, screw, belt or vibrating pan. You must design and interface the feeder so it’s compatible with the vessel above. This step is essential if both are to operate reliably and if the feeder is to operate with minimum power, wear and particle breakage (attrition).

Use flow aids sparingly: Gravity alone is usually sufficient to cause most materials to flow. Once you’ve designed your bin or silo correctly, you probably won’t need flow aid devices anymore. If, however, external or internal vibrators, air cannons or other types of flow aids are required, place and operate them where they’ll be most effective. Again, measured flow properties help determine the locations.

Structural issues

Along with ensuring reliable flow, it’s equally important to be sure that the bin or silo structure is capable of withstanding the static forces imposed by stored bulk solids. There’s a developing body of international standards you can use to determine pressure profiles, which lead to bin designs that are robust and safe.

Importance of routine inspection

Inspect your bins and silos on a regular basis to ensure long life and continued safe operation. Problems such as corrosion, abrasive wear and structural distress often can be corrected if detected early enough. Otherwise, the structure’s integrity may be compromised or flow reliability affected. Similarly, problems of feeder malfunction often can be detected and corrected before they cause more major problems.

Dr. John W. Carson is president of Jenike & Johanson, Inc., Westford, Mass. Contact him at [email protected] and (978) 392-0300.