Plant Services 2015 Workforce Survey: Facing workforce change – Do recruitment, retention, engagement better

For Amanda Saam, the path to greater financial security and better career prospects ran through Somerset (KY) Community College’s Industrial Maintenance Technology program. Saam, 36, graduated from the program in May, and after a summer busy with both job-hunting and spending time with her 13-year-old daughter, she started a job as a maintenance technician at Hitachi in August.

Putting the mojo back in recruiting

Finding it tougher to recruit the talent you need? Maybe it’s not them; it’s you—or more specifically, how and where you’re recruiting. Rethink your strategies and redouble your efforts to reach potential candidates wherever they are, advises Gina Max, senior director of talent management and diversity at USG Corp. She speaks from experience.

“We have a plant in rural West Texas and were really having trouble attracting people there,” Max says. “At one time, years ago, we were the premier employer—that shifted over time. We really stopped and thought about, ‘How can we get back to being that premier employer again?’ We mobilized fast and started to advertise all over the place. We did billboards with really catchy phrases (promoting the company’s pension plan, for example) that got some interest in the area. And then we made sure the local team had tools and resources to spread the word locally about the benefits of working with us. We gave them things like business cards to pass out with our recruiter phone numbers on those. And we started having a better level of candidate flow.

“At our locations across the country, we’ll attend things like a high school fair where we’re talking about our opportunities and what that might mean for a high school student who’s maybe looking for an alternative to college. We’ve targeted things such as military career fairs to find individuals coming out of the military that would be good candidates for our jobs.

“It’s really a dual effort: You need the local team to engage in the process and ensure that our talent brand is strong. Our employees help us find great people. And then we’ve found that we need, secondly, a centralized recruiting structure with real expertise and experience in recruiting and how you find passive candidates. We’ve found that to recruit effectively for our positions, we need recruiting expertise paired with local engagement.”

I love my job,” Saam says. “Where I’m working, it’s a pretty much clean environment, and they have excellent benefits.” Plus, she says, “They really encourage growth within the company, and everyone’s really eager to help me learn what’s going on.”

It’s not a stretch to say that Saam reflects, in a few respects, the new manufacturing workforce. For all of the talk (and hand-wringing) about shifting age demographics in manufacturing workplaces, the full picture of the evolving industrial production labor force has to do with so much more than age.

It’s about women and members of immigrant communities pursuing shop-floor jobs that offer wages that can support a family plus the promise of a variety of advancement opportunities. It’s about midcareer maintenance employees finding themselves rebranded as reliability experts and recruited to join cross-functional collaboration teams charged with ensuring the seamless implementation of new corporate initiatives. It’s about plant owners and managers having to rethink how and when they schedule shift work because prospective employees are seeking opportunities that offer greater work-life balance.

Across plants—across job functions and responsibility levels—the labor landscape seems to be shifting underfoot. And these shifts demand new perspectives on recruiting and retaining talent, because manufacturers need high-functioning, agile, collaborative teams in place to be able to better compete in today’s fast-moving industrial marketplace. How to build and develop these teams? The process starts with a better understanding of the workforce dynamics at play and a multifaceted approach to recruitment and retention.

Now hiring

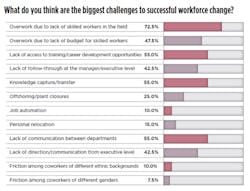

Early results from Plant Services’ new workforce survey (full results will be featured in our December issue) show just how significant of a challenge recruitment is viewed as by those working in industrial production. More than seven in 10 respondents to Plant Services’ online survey said recruiting talent is a major challenge in bringing about successful workforce change. Moreover, 60% of respondents rated attracting young people to the manufacturing field as a high or very high challenge for their specific facility.

The storyline is familiar: Baby boomer retirements and ambivalence among many young people about manufacturing jobs are producing a skilled-worker shortage. But the fact that the problem is widely recognized doesn’t make it any less acute. Research and consulting firm Deloitte estimated in February that the number of U.S. manufacturing positions that will go unfilled because of a lack of skilled labor will grow to 2 million by 2025.

“With the turnover that is coming up, the plethora of opportunities is sitting there,” says Craig Hopkins, project manager at the Versailles, KY-based Automotive Manufacturing Technical Education Collaborative (AMTEC), a partnership between (mostly Midwestern) community colleges and automotive suppliers and original equipment manufacturers. Even today, “We’ve got automotive companies and aerospace companies that are dying for people,” he says. Looking just at skilled maintenance labor needs, Hopkins adds, “If every community college was to produce 20 graduates right now, it would still take us three years just to backfill the current vacancies, and that’s a lot.”

Recruitment: new tools and priorities

So what can be done? Manufacturers aiming to fill their labor gaps must find ways to bust misperceptions about manufacturing jobs to get new workers through the front door, industry advocates say. And that demands proactive outreach to students, their parents, educators, and young people already in the workforce, they contend.

“Employers need to get out to the high schools, the middle schools, and open up their facilities for field trips,” Hopkins offers. “They need to be able to show what type of work is going to be done.”

“One thing we need to keep doing is to try to bring a little glamour to the industry,” suggests Kevin Curry, interim director of professional programs within the University of Kansas’ continuing education program. Manufacturers must focus on selling not only their products but also the value and appeal of what they do on a day-to-day basis, he says.

“I think a lot of people still have the misconception that factories are dirty, unsafe places,” he continues. And indeed, Deloitte’s survey found that while nine in 10 Americans believe manufacturing is essential to the U.S. economy, only a third of parents would encourage their child to pursue a manufacturing career.

Introducing young people to the reality of today’s factories—“almost spotless” facilities employing cutting-edge technologies and operating more efficiently and safely than ever, Curry says—via plant tours, sponsorship of school robotics clubs, and more can be a powerful part of manufacturers’ recruiting efforts. So can participation in high school and college career fairs and professional job expos/networking events, including those focused on women, cultural minorities or military members and veterans. All of these represent opportunities to give an industrial organization broader exposure and let employee representatives tell the company’s story to prospective applicants in a more-personal way.

Of course, compensation is one of the most compelling talking points manufacturers can present. “Talk about the financials that the people are really going to get,” Hopkins says. “Kids want money.”

So do career-changers—another vital labor pool for manufacturers. The promise of earning family-supporting wages in the application of in-demand skills was what drew Saam, a single parent, to Somerset’s maintenance tech program (which was developed through AMTEC).

“I found myself needing a better job to take care of my kiddo and myself,” Saam said after graduating in May. “I had so many people that I knew that had graduated from different programs who just couldn’t find work in their field, so I did some research to see what exactly people were looking for. Come to find out, not only are there not enough women in this field, but there really aren’t enough men, either.”

Both job security and the marketability of the skills and experience they’ll gain on the job are high on prospective applicants’ radar. “The fact that we still have a pension plan in addition to our 401(k) plan, that resonates really well,” says Gina Max, senior director of talent management and diversity at building materials and technologies specialist USG Corp. And on the flip side, she says, USG has also especially promoted its entry-level positions as “tour of duty” opportunities.

“We’ve started to talk more about the fact that you can work for us for a period of time, and we hope that will be for your career; however, that’s not the right choice for everyone,” Max says. “Some candidates will join our team and contribute really well, then make a career move within the company or possibly outside.” A recent company analysis found that about 12% of USG’s employees are in different functional areas than they were in 2010, Max notes. So, recognizing that new hires likely won’t stay in the same role for 10 years as many older workers did, USG touts the that it equips employees with transferable skills.

USG also has seen recruiting success in the past year via one crucial move: creating a mobile-friendly job application. Now, Max says, 20% of job applications are submitted by mobile device.

Today’s recruiting demands add up to a tall order for manufacturers. But Tony Espinosa, vice president of human resources and administration at Des-Case Corp., says a smarter, more-focused hiring approach is an imperative for businesses looking to remain competitive. “Any business’s talent acquisition must include an inclusive strategy to both find and hire great employees,” he says. “This requires a deliberate approach with hiring efforts. What hiring job boards are we using? What industry organizations should we be engaged in that help us connect with different groups? What universities or vocational schools should we be partnering with? Ultimately, how can we build a bridge to the talent that will make the organization great?”

Retention: give ’em what they want

The other vital part of the labor puzzle for manufacturers is figuring out the most effective ways to keep their current workforce engaged. Nearly four in five respondents to Plant Services’ workforce survey (79%) identified retaining talent as a major challenge.

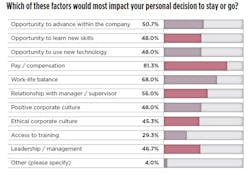

What do today’s industrial production workers want? Good pay, yes: Survey respondents identified it as the top factor that would affect their stay-or-go decisions. But the importance of two other factors in particular—ample career development opportunities and work-life balance—can’t be overstated.

With respect to the first: “A lot of the retaining piece is, once someone comes in, not to say, ‘Oh, they’re really good; I don’t have to do anything now,’ ” says Elizabeth Williams Taylor, a supply chain black belt at DuPont and a region governor for the Society of Women Engineers. “It’s taking the time to understand, regardless of what you hired them in for…what their goals are.”

“Everyone wants to make a difference,” notes Des-Case’s Espinosa. Helping employees—Millennials in particular—see how and why their work matters and how their contribution can continue to evolve can encourage them to stay. That has major cost-savings implications for employers, who are eager to ensure that their training investments don’t walk out the door after a few months. “I don’t think people realize how important work is to people when it comes to morale, general happiness,” Espinosa says.

And yes, says Williams Taylor, some employees will want to spend their entire career as a mechanic. “But that’s not everyone,” she notes. “And if you make that assumption, if you have someone that’s really talented and you just leave them on the side and say, ‘Well they’re really good and they know what to do; give them lots of autonomy,’ but you spend no time finding out what they’re really interested in, chances are they’re not going to stick around.”

Career development for employees doesn’t always have to mean sending them for paid training, Williams Taylor points out. “There are a lot of things you can do that don’t necessarily require money,” she says. For example, one-on-one conversations with a manager are vital to gauge an employee’s interests and to figure out with whom the manager can connect the employee in order to help forge a path toward meeting employee goals.

Adds Des-Case’s Espinosa: “Your people need to grow, and when management is cognizant of that and they have a plan for their employees, what ends up happening is growth and tenure, and then at the two-year point, when they’re finally trained to where they need to be, instead of leaving, they stay, and they start to add significant value to the business.”

Espinosa notes that a lack of development opportunities is one of the top reasons job applicants he’s interviewing cite for leaving their current employer. “When management stops having a plan for their people, people look for someone who has a plan for them,” he says.

Respecting employees’ interests means acknowledging and embracing their outside-of-work priorities, too, and doing more than paying lip service to work-life balance. Plant Services survey respondents rated work-life balance as their second-most-important factor when deciding whether to stay with a company, and more than 80% said it’s a major factor for them in deciding where to work in the first place—and that’s from a respondent base dominated by baby boomers (ages 51 to 70) and Gen Xers (ages 35 to 50).

Sure, most industrial production jobs don’t allow for flex time or work-from-home opportunities. That doesn’t mean, however, that manufacturers can’t do more to meet employees halfway when it comes to balancing work and home priorities.

“If I’m an operator, I can’t work from home; that’s granted,” Williams Taylor says. “But maybe looking at your shift schedules—are your shift schedules maximizing the time your employees can be home with their families? Do you even have to run shifts at all?”

Base vacation time and paid leave matter, too. Giving employees the chance to pursue their non-work priorities and off-the-job passions can go a long way in keeping them around. Williams Taylor points to companies that offer employees a six-week, use-it-or-lose-it vacation block every three to five years—“which is fantastic, because you never know what your employees like to do on the side,” she says. “I worked with a lot of hunters (in a previous plant role), and I think some of them would have gone nuts if every three to five years they could have had a six-week hunting season.”

Everybody in

GE’s recent “What’s the matter with Owen?” series of recruiting commercials smartly captures the evolution of what it means to work for an industrial production company. In one spot, titled “The Hammer,” new, young GE hire Owen receives from his proud dad a sledgehammer that Owen’s grandfather had used on the job. Owen clarifies that while GE does make powerful machines, in his role, he’ll be writing the code that allows machines to talk to each other. His father then mocks him, suggesting that Owen can’t lift the hammer, while Owen’s mother offers assurances that even though their son won’t be physically building anything, he’ll still “change the world.” GE’s tagline at the end of the spot: “Get yourself a world-changing job.”

The slyly subversive ad hits on the head the fact that a huge breadth of talent is needed within modern industrial companies. For employers, it’s no small challenge to create a cooperative rather than antagonistic work environment—to foster respect between different functional teams and among workers with widely varying backgrounds.

Bolstering buy-in

Let’s say you’re charged with helping lead an inter-departmental project team—or with selling your own department on such an effort. How to confront skepticism among the ranks about the value of the effort? Elizabeth Williams Taylor, a supply chain black belt at DuPont, offers a couple of tips.

First, if you’re a facilitator, recognize that you’re probably not the most experienced person in the room, and openly acknowledge that, she says. And to encourage dialogue, try to follow the 60/40 rule: “Sixty percent of the time they’re the ones talking, and 40% of the time it’s you as a facilitator,” Williams Taylor says. “That can help offset some of those situations where you might be trying to set yourself up as the expert in the room when really you’re not.”

Finally, remember that the ultimate success of the initiative depends in part on your staying committed to it for the long haul. “One of the common phrases we hear is ‘program of the month,’ ” Williams Taylor says. “Sometimes people that are executing the work don’t necessarily role-model the tools they’re using or buy in to them themselves, and that can have a big impact.”

At Des-Case, each year a strategy team identifies strategic planning objectives for the coming year and then creates inter-departmental project teams of five to seven employees each to work on these. An executive leader of each team serves as the team’s sponsor and guide; the rest of the team consists of stakeholders in the project—those whose departments will be affected by the team’s work.

How else can plants create a more “everybody in” environment? Company-sponsored volunteer opportunities throughout the year can give employees from different teams the chance to interact and rally around a specific cause or effort. (Seventy-two percent of Plant Services survey respondents said their company offers opportunities to volunteer for charitable causes or events; 60% of those whose employers offer these said they have taken advantage of the chance to volunteer.) Within the facility, even changes as minor as tweaking the cafeteria menu to offer more vegetarian and globally influenced choices can signal to employees that their values and preferences are respected.

“There needs to be a stress that is coming from the leaders and senior management that the collective intellect is how we’re going to be competitive,” says Espinosa. “It’s not just one person’s ideas; it’s a team’s ideas—that is going to make us more competitive and create points of differentiation that are going to help us in the market.”