3 factors affecting staffing in the manufacturing industry and how to overcome them

I have written articles and spoken at maintenance and reliability conferences several times on asset management and other topics related to our profession. And it never ceases to amaze me how those who read articles and attend conferences related to our profession are always seeking that magic bullet, a break-through technology that will drive their organization to best-in-class performance.

Quite possibly, right under their noses, lies the secret to achieving this holy grail we all strive for: developing the people who work for them into peak performers.

Don’t get me wrong, having best-in-class practices and programs is necessary if you want best-in-class results, but all of the innovative and well-oiled programs will not get you very far without competent and driven people to administer them.

Triple threat of challenges

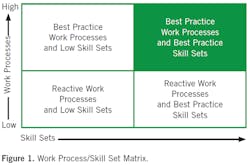

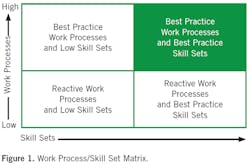

In 2016, I facilitated a workshop at SMRP’s annual conference on “The Journey to World Class Asset Management.” There were 40 people in attendance. I placed the slide shown in Figure 1 on the screen and discussed the importance of having both best practices: processes and highly skilled employees.

I remember there was a maintenance and reliability leader from a well-known company in attendance, who appeared to disagree with my viewpoint. It seems he thought turnover was inevitable, therefore his organization concentrated on building systems that were literally bullet-proof. In this way, when a person left, the company could just hire someone new and teach him or her the system.

I asked what type of turnover the company saw, and I believe, if my memory serves me correctly, it was somewhat on the order of three years. I congratulated him for building such a robust system, but then asked this simple question. “What if you took that same best-in-class system and worked to create an environment where employees were compelled to stay a little longer, say four to five years? What would that be worth to the organization?” It’s possible that he didn’t like my answer or possibly did not see the value of the class because he got up shortly thereafter and left the workshop.

These days maintenance and reliability leaders face a triple threat of challenges:

1. Employees are not staying with one company as long as they used to. A 2018 Bureau of Statistics Report cited that the median age of tenure for manufacturing employees stood at approximately five years1, and this number was skewed toward older employees. If you only look at younger professionals, the real lifeblood needed for future improvement, the number drops significantly. If you hire young professionals and develop them, say as maintenance or reliability engineers, and their ambition is to eventually be in management, you risk losing them to another organization or to a production management role inside your organization within a few years. That goes for employees who typically are less transient, locals who grew up in the community. While they might not pick up and move across the country to find a new opportunity, they certainly are more apt to change employers than their parents were. And if they are peak performers, you want to keep them within your organization.

2. The knowledge base of our profession is reaching retirement age. If you attend a large maintenance and reliability conference, look at the thought leaders who are giving the presentations. Alarmingly, there are too many that are my age, the last of the Baby Boomers. For many people, keeping them engaged and therefore interested and motivated, can be accomplished by continually giving them the opportunity to learn and develop new skills. And once new skills are developed quickly allowing them to apply what they have learned.

3. Our profession is having difficulty attracting young people to a career in maintenance and reliability. Again, go to a maintenance and reliability conference and see the number of grayhairs and graybeards in attendance. Not only are we having trouble getting young men and women interested in the skilled trades, but we also struggle getting young professionals into our salaried workforces. Part of the reason is one of marketing and exposure. When I was a young engineer in college, I had no idea what the maintenance discipline had to offer. And I would not have believed in my wildest dreams 29 years ago that I would be doing what I am today as an engineer; teaching and preaching the gospel of asset management more as a mentor and a coach, then a doer.

Start thinking strategically

So, what might one do to protect against the risk of losing these, their greatest assets, let alone to be able to hire tomorrow’s talent in the first place? The answer is simple: think strategically! Reliability leaders must attack this challenge like they do any other asset management opportunity, with intentional purpose and a plan. Start by thinking about what motivated you in your career. Most people are motivated by one of two things, or possibly both: money or opportunity. Opportunity can take the form of promotional advancement or just feeling like you are making a difference. Take a look at a typical maintenance organization (shown in Figure 2), and you will see why this might be a difficult challenge.

For those within the organization whose ambition is to advance into a leadership position, there are limited opportunities, unless you plan on retiring soon. So, if you hire a young reliability engineer out of college, or one of your planners or supervisors wants to someday become a manger, he or she has three choices: wait for you to retire, take a leadership position within the organization in operations or engineering, or take an opportunity with another company. Selfishly, if this employee has potential to become a great leader, options two or three do the maintenance organization little benefit. And certainly, option three can do your organization harm, as potential leaders are in short supply. I’m sure some of you can relate to the veritable merry-go-round staffing can present. It seems like you just get someone hired and trained for one position, and you have a vacancy somewhere else. It’s a never-ending saga, and takes a great deal of valuable time and energy to just tread water.

So, if you hope to keep your team engaged, may I suggest you create opportunity through giving those who work for you chances to take the lead on projects. It serves a two-fold purpose: it gives employees a sense of accomplishment from the feeling that they took ownership and made something happen, and it gives them a chance to develop their skills in a somewhat safe environment. As you well know when you are the maintenance manager or reliability leader, the buck stops at your desk. Sometimes failures are seen at the highest levels of the organization, whereas if you allow your employees to own an individual initiative, sometimes setbacks can be hidden under the umbrella of the overall strategy.

Last year, I wrote a cover story for Plant Services on training future leaders, and I discussed linking business needs with the right person. When you are considering how to engage a workforce, discovering what someone is passionate about, then creating opportunity around this employee’s passion is key to keeping his or her satisfaction level high. I have one reliability engineer who works for me who does not want to be a manager. His passion lies in managing predictive maintenance (PdM) technologies, being out in the field solving problems and helping others. We have a business need to achieve “best-in-class” results from our predictive maintenance effort, and certainly a “world-class” PdM program improves the odds that we will have less downtime and lower maintenance costs, so it’s a logical choice to allow this person to lead our effort.

His training and development centers around PdM technologies, and he is slowly gaining certification in a number of technologies. One of our latest initiatives is to develop better in-house balancing expertise. The reliability engineer in question has taken the initiative to use one of our out-of-service fans as a balancing trainer, so that he and one of our PdM technicians can develop their skill. The technician in question actually works a swing shift, so within a year, we hope to avoid times where we have to make an emergency call to the contractor who we currently outsource the majority of our balancing needs to. Look for these win-win situations where you can improve the business, while allowing one of your employees the chance to own and run with an initiative that they are passionate about, and you have created an atmosphere where engagement can take root.

Don’t forget the craftsmen in your organization. Be on the lookout for the next potential planner or maintenance supervisor. Craftsmen make great candidates for these positions. Not only do they know the business, the people, and the culture, but by hiring from within, it creates incentive for the next person who might want to consider a growth opportunity.

Also consider craftsmen who are starting to show their age and find difficulty with the rigors of the craftsman position. We have found opportunities within our computerized maintenance management system (CMMS) group for those who have to go to light duty due to injury or age-related degenerative condition; they are doing useful work such as equipment walk-downs and CMMS data entry. Be aware of those who are toxic to the culture. I guess it is possible for them to have a change of heart, but if they were bad-mouthing the organization as bargain unit employees, chances are they will continue to do so from the salaried side.

The fact of the matter is that sometimes it will come down to money. If you have received promotions on a regular basis throughout your career, you possibly have tripled or even quadrupled your salary over a 30-year tenure. But if you are stagnant in your growth potential, doing the same job as you were 30 years ago, chances are your salary has doubled, at best, with the annual two to three percent increases that are the norm these days.

Be prepared to pay for performance. Ask yourself who you would hate most to lose, and make sure they are the ones who receive the maximum salary increase at performance review time. In his 2001 book Good to Great, Jim Collins writes, “People are not your greatest asset, the right people are!” And by all means thank your employees for their contributions. A little appreciation goes a long way and when budgets are tight, appreciation doesn’t cost you anything. If employees feel valued and appreciated, it might make the difference between them staying put and listening to that next offer. Remember what Richard Branson was quoted to have said earlier this decade: “Train people well enough so they can leave; treat them well enough so they don’t want to.”

Knowledge transfer = power

In the old guard mindset of maintenance, knowledge equaled power. You worked hard to gain knowledge and expertise, and knowing something others did not gave the appearance of value. If a younger possibly harder working individual knew everything you did as a more seasoned employee, you risked being downsized, especially since you usually earned more money. But I would argue in today’s more collaborative approach to business, the ability to teach and transfer knowledge equals power.

I personally think that each and every individual working for you should have a written training and development plan. Take the planner position for instance. Some organizations treat their planners as a second maintenance supervisor, asking them to fill in for supervisor vacancies or running jobs alongside the supervisor on shutdowns. I do not agree with this mindset; rather, think of the planner as a position closer to that of the reliability engineer. While planners many times come from the trades, I would like their jobs to focus on getting the craftsmen to use precision skills; therefore, I want them to think about work differently, than the “get it done and get it running” mindset many maintenance cultures are stuck in. I would also like their use of the CMMS to approach that of best practice.

To accomplish this goal, the planner should have a training and development plan that focuses on these skills. Figure 3 is an example training and development plan one might have for the planning position. '

I am a firm believer in what I call applied learning. Once employees have completed a training course, they should be prepared to apply what they have just learned. As an example from the above training and development plan, as soon as the failure modes identification training class is taught, have the employee examine failed parts to put that knowledge to work; or, in the case of the precision skills course, an assignment might be to have the employee write two or three precision skills job plans or task lists right away, while the course principles are still fresh in his or her mind. If you are not careful, employees will go back to their jobs and soon forget what they have just learned. When I send an employee away to a conference, it is not considered a vacation; I like to ask the employee to come back with three ideas on how he or she can improve our effort, and these ideas become goals on the following year’s performance objectives.

Giving people an opportunity to develop their skills is a double-edged sword. As they become more proficient, gain knowledge, skill, and confidence, they are likely to get more opportunities thrown their way. And if they are working with contractors and service providers outside the organization, shrewd leaders will see their potential and possibly be tempted to lure them away with a substantial raise.

But I still prefer to develop my employees to their fullest potential and believe those who put a great deal of time and effort into training and development will be further ahead than those who don’t. I like the old story I heard about the CFO and the CEO having a conversation about the training budget. The CFO said, “what happens if we train our employees and they leave for better opportunities?” to which the CEO replied, “what happens if we do not train them and they stay?”

Attracting (and retaining) the next generation

So many people are talking about the craft skills crises that it has gotten more than its fair share of attention. But just as important, and far less often discussed, is the difficulty our profession is having attracting young talent to the maintenance and reliability field. Few young engineers and professionals understand the unique opportunity that is available to those pursuing a career in maintenance and reliability. Twenty-nine years ago, when I left college, I would never have dreamed that the opportunities I have been given were even possible.

What are you doing strategically to recruit tomorrow’s potential leaders and reliability engineers onto your team? Do you or a member of your staff attend job fairs that target colleges? Beyond this, are you taking advantage of possible opportunities to speak at colleges about our profession? Getting college professors to give up a lecture hour and turn over their classes to you is not an easy matter, but it is possible if they feel you offer a real-world learning opportunity for their students.

If you are given the opportunity to speak in front of a class, don’t have it become a sales pitch for your organization. Make it a sales pitch for your profession, as well as a learning opportunity, and you are more likely to get invited back. This might be the first time these students ever learned about what a career in maintenance and reliability has to offer, and if you are passionate and can pique their curiosity, you might leave them with the impression that you would make a great mentor for their careers. I would target a freshman or sophomore class for two reasons: a larger class size gives you more opportunities to get someone interested in maintenance and reliability as a career choice and, by targeting the younger students, you could possibly get some of them on as a co-op or summer student for a year or two to see what potential they might have for a full-time position.

Looking forward

These days, maintenance and reliability leaders face a triple threat of challenges when it comes to staffing. Thinking strategically and creating career development paths for all members of your team might be the difference between struggling to stay afloat and sailing away toward best-in-class performance!

REFERENCES

1. Table 5: Median years of tenure with current employer for employed wage and salary workers by industry. Employee Tenure in 2018 – Bureau of Labor Statistics.