Own reliability at your facility and make decisions to continuously increase it

Within any organization, employees are expected to improve their skill sets and therefore their value to the organization. A good employee will expect this and seek to find available areas which are fulfilling for the employee and useful for the organization.

For many organizations, this is a two-edged sword. On the one hand, the improved employee is more useful to the organization; the downside of this is that the employee is now more valuable, and often to those outside the organization. In the current career climate, the average tenure of a maintenance employee is 5.3 years (based on a six-year study from the Bureau of Labor Statistics). So how can you maximize the reliability efforts at your facility, given the relatively brief tenure of the skilled maintenance worker?

Before going any further, I need to admit that my involvement in reliability is the result of a second career. I was previously involved in the security industry (not to be confused with securities) as a small business owner. As such, I dealt with multiple clients, most of whom would best be classified as mid-level corporate management, and often from a maintenance department. I enjoyed dealing with many of these people, but the sad truth is that I spent most of my time “training” them in that particular area of their responsibilities.

Unfortunately, in most cases, about the time we reached a comfort level in our professional relationship, they were proud (usually) to inform me they had accepted a promotion or transfer and from now on, I would be dealing with someone else. The security “training” had to begin again. And consider that this was not technical “training” requiring these folks to understand how to be able to perform a particular operation. It involved just understanding what was required to satisfy the security need of the moment.

Consider, if you have not already done so, how much your organization (or someone else) is investing in the engineers, technicians, and tradesmen who maintain the operating capabilities of your company. How many years did they spend learning to perform their functions? And how many years until they reach the end of their tenure with you?

Of course, you may retain some people longer than the 5.3-year average tenure mark, but others won’t make it even that far, and still others will seize opportunities which you (your company, at least) provide and not necessarily move along, but move up. In that case, you may retain their knowledge and even their ability, but you lose their availability. And of course, even when you succeed in maintaining your personnel, death, disability, old age, and retirement are waiting to steal them away.

Is there an answer? Possibly! It may not be the answer for all, but outsourcing is at least one workable solution. However, the concept is about more than just putting dollars into the columns of other companies’ ledgers. It’s about developing and maintaining professional standards in the reliability and predictive maintenance communities, and more importantly about achieving safe and reliable facility operations for your facilities.

Okay, you might ask, “What’s the difference? Why is the reliability and predictive maintenance operation of an outside organization going to do a better job of achieving the elusive reliable facility operation? I have vast resources from my organization. Anything you can buy and learn to use, so can I.”

Quite true! But…do you have personnel already qualified to perform the required reliability responsibilities? Are they able to devote the time required to collect, analyze, report, and distribute the data required to maintain the level of reliability requested? Are they part of a department or group which will work together using the collected data to avoid unplanned outages, plan maintenance when required, and determine root causes of failures and faults? Are they (or are they willing to become) reliability professionals willing to work with all comers to achieve plant reliability?

Now, I ask you to allow me to offer you my concept of how to achieve reliability. And let me state that this is more a view from a worker viewpoint more than a manager’s. My time in the reliability and predictive maintenance communities has been spent collecting data, and then generating reports and action plans from the collected information. My job title is and has been Field Service Technician. I’ve done many alignments, trim balanced a lot of equipment, made motor electrical connections, scanned MCC buckets with IR imagers, and collected static and dynamic data from motors in the field. I consider myself a technician (i.e., a grunt), and I write and speak from that perspective. I also was once a small business owner, which may color my perspective somewhat (but small was really small).

Building an ideal reliability program

The following is an ideal situation. I have never personally experienced Nirvana (a.k.a, an ideal situation), so I am going to use as a hypothetical example a 400 Megawatt coal fired power plant. I collected route vibration data from a plant of this description for about ten years, and I am relatively confident of the vibration time to collect, analyze, and report. However, I am estimating the amount of time that it might require to perform the other testing recommended, based on plant layout and experience at other locations. All stated days are for one year of data collection and reporting (see Table 1).

Vibration Analysis. Monthly data collection for critical, essential, and important equipment (any continuously monitored machines should have data reviewed at least monthly, even if no alarms have occurred). Secondary and non-essential equipment should have data collected quarterly. We estimate data collection taking 40 days annually. We would allow up to 52 days for analysis and reporting of findings.

Infrared Thermography. Survey equipment running with normal to full load every six months. Follow-up surveys should be conducted within one month following repairs. Equipment with voltage greater than 480V should have IR windows installed to allow observation of connection points. This may require more than one window per cabinet. We estimate spending 8 days conducting surveys. We would allow at least 10 days for analysis of data collected and report generation.

Tribology. Oil sampling from critical equipment monthly. Essential and important equipment should be sampled quarterly. We estimate the sample collection would take 19 days, and that reporting on the analysis would take at least 17 days.

Ultrasound. Should be used in conjunction with lubricating machines, and opening electrical cabinets. We estimate conducting the surveys would take 15 days, while the analysis and reporting would take at least 5 days.

Static Electrical Testing. Should be conducted on critical, essential, and important motors at least annually when the equipment can be shut down. This should be scheduled to allow collection, analysis, and reporting to be completed and disseminated in time to enable service be planned as required. We estimate performing these tests would require 7 days. We would allow at least 5 days for analysis and reporting of findings.

Dynamic Electrical Testing. Install an electrical port (EP1000) to allow dynamic electrical testing to be performed without shutting motor down for connection. This requires connections to the existing current transformers (CTs) and the potential transformers (PTs) located in the low portion of the main power module, in order to collect power and current data simultaneously. The dynamic testing should be conducted monthly for critical and essential equipment, quarterly on important equipment, and semi-annually on secondary and non-essential equipment. We estimate the testing would require 47 days and the analysis and reporting would require at least 38 days.

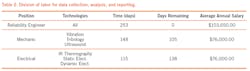

Using a five-day work week, and assuming eight holidays per year, we find that the year 2020 contains 253 working days. Our estimated time to perform this testing for this theoretical location is 263 days. Wow, we can’t even get it done in a year! At least not using one technician, and assuming all the estimates are accurate. And there is certainly no time for additional, follow-up, or troubleshooting tests (see Table 2).

Costing the ideal reliability program

Okay! Here is where it can really start getting fun. Let’s do some comparisons. Based on independent research, I found that the national average salary for the position of reliability technician can go as high as $76,000 annually. The average salary for reliability engineer averages was of course higher, at $103,650. And why, you might ask, are we investigating what the average salary is of these gentle folk? Well, our theoretical coal fired power plant, if they decide to go with the “ideal” program, is going to need to hire at least one or the other to operate the program.

I’m a cheapskate (just ask my kids), so let’s use the technician salary for this theoretical program. Using one person, you might manage to accomplish each of the objectives in the program in one year, or come close enough to be pleased. But do you already have a person who is qualified, trained, and certified? If not, and most would not be able to say yes with all of these categories, then you will need to hire one. This means you will likely have to pay top dollar salary, and may have to provide other initiatives to get someone on board.

But wait a minute, are you a union shop? Which union will you need to hire through, or can you? I’m not intending to bad mouth unions or union tradesmen, but this is one of those instances where the job description does not belong to one union or another. It seems part millwright and part electrician.

So what’s next? Maybe you should bite the bullet and hire the engineer. That would most likely solve the union issue of hiring someone. But then, what if your engineer goes out to collect data? Is that going to be an issue with your unions? Maybe not in all, but in many plants and places, this would be a big issue.

Potentially, you could hire the engineer, and hire or train one technician from the crafts which have responsibilities for your machines. Our theoretical plant has electricians, instrument technicians, mechanics, and operators on staff. I don’t know if their unions will allow for multiple disciplines within their memberships, but let’s assume conservatively that this mix of personnel is satisfactory: one reliability engineer (dept. manager/supervisor/analyst); one mechanic (vibration, tribology, ultrasound technician); and one electrician or instrument technician. Your Reliability Department has now grown from one to three!

Using the previously mentioned salary averages, you now have pushed your annual budget from the low of $76,000 to $255,650. You would need (almost certainly) training in their different responsibilities. Put that in your budget! You will need work, storage, and office space for them, whether re-allocation of existing resources, or additional space. Include that in your budget! You will need adequate equipment required for each of the reliability fields. And don’t forget those hand tools and supplies needed for their tasks. Add that to your budget!

As you can see, beginning a reliability program is not lightly done. The benefits can be enormous! But it will not happen overnight. It takes time to develop, and it requires up-front investment. Should you make the needed investment, it requires a continuing commitment to the program and in most cases requires constant advocacy. Starting a Reliability Department from the bottom up is not for the faint of heart!

Maybe at this point we should put a big check mark in the outsource column. At least, if you outsource, you don’t have possible union in-fighting over whose job it may be. Also, you don’t have the headache of training, maintaining certifications, or retaining qualified technicians. Let your contractor fight those battles. So let’s give the outsource column another check mark!

Yet another consideration is the multi-tasking which would be required if one technician were to provide 100% of the reliability services discussed for our “ideal” situation in our theoretical facility. They would need to be qualified (and certified?) in vibration analysis, thermography, tribology, electrical testing, and ultrasound technologies. (I’ve been at this for 17 years, and I only have earned certifications in two of these technologies, and have zero experience in two others.) One thing for nearly certain, you won’t hire anyone qualified in all of these areas off the street unless you are more than lucky.

Consider outsourcing to own reliability

The previous statement brings me back to the concept of outsourcing. At the very least, it is a way to pass the various staffing dilemmas off to someone else! On a more serious note, outsourced reliability services make business sense. You have the opportunity to make use of specialists in each area without the need to hire, train, and retain additional employees.

Should you have the necessary specialist employees in your organization, make good use of them! You have a tool available to you that most can only dream of. But you may need to bring them together as a team, rather than operating in “competing” departments.

It’s all about OWNING THE RELIABILITY of your facility and making decisions to continuously increase it!

Timothy A. Morrison is a field service technician and vibration analyst for Hibbs ElectroMechanical Inc. of Madisonville, KY. He began his career in predictive maintenance with Mohler Technology Inc. in 1999 and has been involved in the vibration consulting program at Hibbs since 2003. Tim is a vibration analyst and a Level II Infrared Thermographer, and is involved in the analysis of both static and dynamic motor testing. Contact him at [email protected].