Motivation starts with you: Do you truly understand your team's needs?

Being a motivator means creating eagerness among others to act, supporting their decisions, and accepting challenges. Motivating people starts with understanding their needs. As individuals, we do things to satisfy needs within ourselves. To obtain insight and to enhance our ability to lead others, we must understand needs and how needs motivate.

In this article I’ve included discussions on prominent theories from behavioral science. These theories are well-known and respected, and writings about them have been peer-reviewed. They are provided to help you frame your thoughts when wrestling with needs and motivations. If one of the theories resonates with you, use it as your model. I also encourage you to research these theories more deeply to further develop your knowledge and skills.

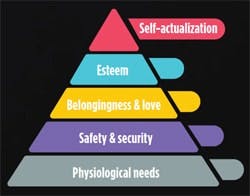

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Perhaps the most familiar needs model is Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, developed in the 1940s and published in 1954. Maslow determined that there are five general levels of needs. The general levels were grouped into these five categories and arranged in order from the most basic to the most aspirational for individuals. From bottom to top, the five levels of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs are:

- Physiological needs

- Safety and security

- Belongingness and love

- Esteem

- Self-actualization

Let’s go over the definitions of each need:

Physiological needs are a person’s most basic biological needs. Examples include breathable air, food, water, shelter, and sleep.

Safety and security needs refer to a person’s physical safety, health, and economic security. People need to provide for themselves and their families. Within an industrial environment, this has implications when it comes to working conditions, safety precautions, and business viability. Are workers provided with personal protective equipment (PPE)? When safety issues are reported, do supervisors and managers deal with those issues? Is the plant or company planning to or likely to close?

Belongingness and love needs refer to the social aspects of a person’s life: family, friends, and intimacy. Beyond the basic needs (physiological, safety-related, and security-related), people begin to have latitude in determining whether their current situation is comfortable. Belongingness and love needs address whether a person feels as though he or she fits in and is accepted by others. People are social beings, and they need to interact with and be accepted and appreciated by those around them.

Leaders have a major influence on this need. Belongingness and love are a foundation for building trust. If people are disrespected or talked down to, they will not be inclined to trust leadership or to be engaged team members.

Esteem refers to a person’s need to be recognized for his or her performance, competence, or mastery, and/or that person’s status within the organization. When people feel comfortable because their belongingness and love needs are effectively met, esteem appeals to the individual’s desire to feel valuable and appreciated. People want to feel that they are important. Overtly telling people you appreciate their continued good performance and their importance to the organization is easy to do. It shows that you trust, respect, and appreciate their expertise. It also can raise their status within the organization.

Self-actualization reflects an individual’s desire to grow and develop to his or her full potential. This goes beyond earning a paycheck for being good at a job or being recognized for competence or mastery of a skill. This is about a person pushing the limits of his or her abilities. A person never becomes completely self-actualized because self-actualization is a moving target – a continually evolving set of personal objectives. As one set of skills is mastered, a self-actualized person resets his or her objectives and attempts to conquer another set of skills or capabilities.

Application of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs:

- Lower-level needs must be sufficiently satisfied before the next-higher level of needs can be used to motivate behaviors.

- Generally satisfied needs have less power to influence behaviors than unsatisfied needs do.

- Lower-level needs don’t go away, but people become less conscious of them when more-powerful needs are in play.

McClelland’s Needs Theory

David McClelland published several research papers from the 1950s through the 1990s. McClelland and his research team developed McClelland’s Needs Theory based on three types of needs;

- Achievement.

- Affiliation.

- Power.

People with a need for achievement like to find solutions. They tend to set moderate goals with moderate risks. That approach creates a greater chance of being successful. This type of person has a strong desire to receive performance feedback. They are concerned with career advancement; they want to do their job better and accomplish significant things. They can be more risk-averse or tentative because they don’t want to fail.

People with a need for affiliation crave social interaction. They value camaraderie and positive relationships with co-workers. They are concerned about how others feel about a situation or circumstances. If there is a perceived problem with a relationship, the person with the need for affiliation will seek to repair the broken relationship.

People who have a need for power will try to influence and control other people. They seek out leadership positions because they want to be responsible, be in charge. They are often viewed as outspoken, forceful, and demanding, and they value being able to persuade others to see things their way.

In McClelland’s Needs Theory, the needs categories are not hierarchical. People also are not placed into only one of the categories. A person can have strong needs in one area but also exhibit significant needs in other areas, whether needs in their strong area are satisfied or not. People will have a blend of needs from each of the categories to some degree. The blend of needs for each person provides an individual profile that can be considered when developing motivational approaches to influence behaviors.

McClelland proposed that those in senior management positions should have a high need for power and a lower need for affiliation. Individuals with a strong need for achievement can make good department or functional managers or small-business owners, but they may not be well-suited for top management positions if they don’t also have a need for power.

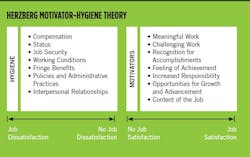

Herzberg's Motivator-Hygiene Theory

In 1959, Frederick Herzberg, a professor at Case Western Reserve University, and his research team were studying human aspects of improving task efficiency and job satisfaction. The team came up with the Motivator-Hygiene Theory (sometimes referred to as the Two-Factor Theory). It has been the most duplicated research in the field of behavioral science. I view this theory as among the most practical for thinking about needs and motivations that affect performance.

Herzberg’s original work was based on researching job attitudes. He surveyed 200 accountants and engineers. (I’m thinking he was looking for the least excitable people on the planet.) He asked two basic questions:

- When did you feel good about your job, and why?

- When did you feel bad about your job, and why?

The answers to these two questions were categorized as satisfiers and dissatisfiers. Satisfiers were factors that motivated people, that made them excited about their job. Dissatisfiers were factors that were demotivating, that made people feel bad about their job. During the analysis, the team found it rare that any factor was both a satisfier and dissatisfier. In describing the findings, Herzberg and his team used the terms motivator factors and hygiene factors.

In Herzberg’s model, motivators are the features of a job’s content, such as responsibility, recognition, self-esteem, autonomy, and growth. When a person feels he or she has more influence over his or her day-to-day activities, that individual will be more motivated, will exert more effort, and will perform at a higher level.

Hygiene factors are features of the work environment or work context (e.g., administrative policies, wages, job security, and working conditions). Herzberg referred to hygiene factors as things that might result in a “kick in the ass,” or KITA. His research suggested that if a hygiene factor is improved, a person’s dissatisfaction with his or her job will decline. And when dissatisfiers are reduced, people become more receptive to motivators.

Dissatisfiers are stressors. People will put up with a certain level of stress, but as the quantity and severity of stress increases, a leader’s ability to motivate decreases. This makes sense if you think about some of your own work situations. No matter how great the job content, there is some level of the job’s context that is not worth enduring. The pain of dissatisfiers can outweigh the gain of the satisfiers.

Examples of hygiene factors:

- Policies and administrative procedures – adequacy or inadequacy of organizational policies and policy management. Policies and procedures must be reasonable. If there is a lot of ambiguity or if there are gaps and overlaps in guidance, people will feel unsupported and vulnerable to shifting priorities and directions.

- Supervision – the qualities of the supervisor. When superiors seem out of their depth, lack interpersonal skills, or otherwise create problems for their teams, they do not instill confidence.

- Working conditions – the physical environment of the job site, as well the amount of work. Do people have the tools needed to do their jobs? How are the lighting, temperature, and general cleanliness and organization of the workplace?

- Interpersonal relationships – interactions between the employee and others in the firm, e.g. supervisors, peers, or those in other departments or functions.

- Compensation – pay and benefits. Are they reasonably in line with regional, industry, or common levels for the position?

- Job security – a feeling that the organization is stable and that there is going to be a place to work for the foreseeable future.

- Status – the feeling a person has about his or her job and importance to the organization. This can be indicated through overt expressions of status such as delegated authority, a reserved parking location, etc.

- Personal life – non-work-related aspects of a person’s life. Do workers feel they work a reasonable number of hours? Are workers able to enjoy their off-time and not take job stress home?

Examples of motivators for individuals include:

- Achievement – completing a job, solving problems, and seeing the results of one’s efforts.

- Recognition – being identified for a personal accomplishment or a job well done.

- Type of work – the positive or negative content of the activities being performed: Is the work interesting or boring, varied or repetitive, creative or mind-numbing?

- Responsibility – having control over one’s work or being given responsibility for the work of others. Authority to generate results is implied to be part of responsibility.

- Advancement – an actual upward change in position or status.

- Growth – learning new skills with greater possibility of advancement.

Productive leaders will find that they can affect most motivator and hygiene factors directly. Some elements, such as compensation, cannot be directly affected. But a leader can affect these indirectly. For instance, a supervisor probably can’t increase his or her team members’ wages without higher-level approval. But a supervisor can help a team member improve job skills or capabilities that allow that person to compete for a position with better compensation.

The Herzberg Motivator-Hygiene Theory is one of my favorite tools for assessing needs and motivations. As with all of these theories, they point you in a direction, but you need to apply productive leadership to implement changes to drive improvements.

Final thoughts

In the final analysis, nobody wants to work in an organization full of unmotivated people. A productive leader must understand that needs drive motivation. Constantly look for opportunities to increase motivation by learning about needs theories and finding ways to satisfy needs. Get familiar with your team members. Learn what their needs are. Apply good leadership practices to motivate and help them satisfy their needs.

To illustrate the importance of attentiveness and responsibility, I want to discuss a real-world example I witnessed. This accident took place inside an industrial plant; I was in the facility on an unrelated project.

The client organization was installing new technology in its production facility. The project included fabrication and installation of an elevated platform that would be supporting some large and very heavy system cabinets.

As an outside person walking through the plant, I noticed that the platform did not have handrails around the perimeter. A worker on the platform was not wearing fall protection. I pointed the clear safety hazard to a manager and later to a supervisor.

A short time later, the worker absentmindedly leaned on what he thought was a railing. He fell off the platform to the concrete floor 18 feet below. The worker survived, but he was seriously injured. He endured a substantial amount of painful recovery time. The plant was hit with higher insurance costs and a “regulatory colonoscopy” from OSHA, and the project’s completion was delayed.

Had leaders been attentive to safety hazards and taken responsibility to act, the accident would not have happened.

Good supervisors manage their time and perform management by walking around (MBWA). Leaders need to dedicate time to this activity to be aware of what’s going on, and they need to take responsibility for addressing issues they spot or that are brought to their attention.

In the type of situation described above, people tend to get complacent. A productive leader needs to be attentive and must take responsibility for identifying failures and lapses and acting to prevent undesirable events from happening.

In the plant example, the real problems are not the individual actions, although operators and craftspersons bear some portion of the responsibility for their actions. The real problem is the complacency of executives, managers, and supervisors who allow people with whom they work to cut corners.

It is human nature for individuals to seek ways to make things easier for themselves. Every time a person cuts a corner and there are no negative consequences, there is a payoff. The more times it happens, the more payoff is accumulated. But this is a game of probabilities. One person may take shortcuts and go an entire career without experiencing a major issue. More likely, the shortcuts that one person takes will have a contributing effect that will exacerbate the effects produced by everyone else who is cutting corners. The more people who are complacent in an organization, the more likely it is that there will be major accidents or events.

There is never one root cause for catastrophic events. For every person who is blamed or thought of as the person responsible, there are several executives, managers, supervisors, and/or other workers who also were complacent.

Eliminating complacency, therefore, is everyone’s job. Don’t be part of the problem; don’t cut corners.

The moral of the story is that taking responsibility is a skill that can and should be learned. When we look to hire or promote a person into a leadership position, we should be checking for evidence of the candidate’s history of taking responsibility.