Tuning PID loops is not always quick and easy. Indeed, several steps are involved in the proper tuning of a PID controller – steps that will deliver consistent results and optimal controller performance. Arguably, the most important step is testing. When properly performed, a test can expose the dynamic relationship that exists between a controller’s process variable (PV) and its controller output (CO). The data from such a test allows for calculation of an accurate model and setting of tuning parameters that will be best-suited for controlling the process.

A common problem for practitioners is determining which of the available testing options is best for their situation. As is often the case in the world of automation and process control, the answer is: It depends. For starters, how fast does the loop respond to change? How sensitive to change is the material being processed? How much time can you spend making changes while testing? These and other considerations are fundamental to the selection of an appropriate test.

Listed below are four tests that are used to reveal dynamic behavior and tune PID control loops. The basic pros and cons provide a useful starting point for determining which test is best for your PID controller tuning needs:

Step test

Among all of the options the step test may seem straightforward, but it presents a few notable challenges. Such a test involves “stepping” the CO from one constant value to another. It should result in the PV moving from one steady state to another steady state, and the size of the change should be large enough so that the response is clearly distinguishable from any noise apparent in the process. If modeling and tuning software is not available, then the step test may be the only viable testing option, as model parameters can be manually calculated using a trend of the associated test data. On the downside, however, because a steady state is required at both the start and the end of the test, the step test is typically time-intensive. Furthermore, any results can be invalidated if disturbances occur while testing.

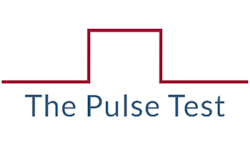

Pulse test

The pulse can be thought of as two step tests performed in succession, in opposite directions, and without the steady-state requirement in between. It starts with changing the CO value and moving the PV in one direction until a clear response is evident. Once the PV response is evident, the CO is then stepped in the opposite direction – often before the process establishes a new steady state. Ultimately, the CO is returned to its original steady-state value. This option is more thorough than the step test, as it moves the process in opposite directions, typically revealing different dynamic behavior within a process (e.g. heating vs. cooling). However, the pulse requires the use of software to accurately calculate model parameters.

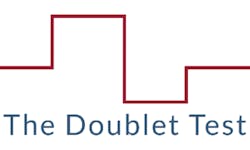

Doublet test

Among the four options discussed here, the doublet test is the most complete and least disruptive. On the surface, it has the appearance of two pulses performed in succession and in opposite directions. Note that the overall impact of the doublet test on the process is limited as the first and third PV changes are modest in size and are typically smaller than needed for a single pulse test. It is the doublet test’s second PV change that is the difference-maker. The second change is double the size of the two smaller adjustments, and it spans the PV’s initial steady-state value. Collectively, the changes provide a comprehensive understanding of the process’s dynamic behavior, revealing behavior across a wider range of process regions.

PRBS

The pseudo-random binary sequence (PRBS) test is an option that is best suited for sensitive processes – those that cannot sustain significant or sustained changes to the PV value. It involves a sequence of CO pulses that are uniform in amplitude, alternating in direction, and of random duration. Each CO pulse drives the PV just beyond the level of noise in the process. While individual pulses are smaller in nature and produce data that is only moderately functional from a tuning standpoint, the collection of PRBS pulses can produce data that is highly functional. In terms of negatives, this testing method is complex and requires a significant investment of time. For processes that cannot withstand large changes, however, the PRBS offers an effective means for capturing the data needed to improve PID loop performance.

Each of these testing options is used in industry; each has its clear pros and cons. Assuming that the control loop can be held at a steady state at the start and end of testing, then a manual step tes thas been shown to produce consistent results. For the other PID controller tuning options referenced in this post, the use of software is recommended. Software generally prescribes a standard, repeatable procedure when tuning, which is a good practice. Additionally, select software products have proved to calculate accurate models in spite of excessive noise and oscillations.

For more on PID Controller Tuning and testing, see these articles:

About the Author

Alexis Gajewski

Senior Content Strategist

Alexis Gajewski has over 15 years of experience in the maintenance, reliability, operations, and manufacturing space. She joined Plant Services in 2008 and works to bring readers the news, insight, and information they need to make the right decisions for their plants. Alexis also authors “The Lighter Side of Manufacturing,” a blog that highlights the fun and innovative advances in the industrial sector.