Once there was a plant, heavy with United Steelworkers (USW) members. Business slipped, and the company started down the path of restructuring. Guess what happened?

Collective bargaining negotiations broke down. Union members said there was no way the plant could be run without them. “We maintained that it could be, although we'd rather it be with them,” says a manager with the contract firm that took over all maintenance operations. “Despite our repeated efforts, the unions decided they would not talk to us.”

Union: busted. More than 100 new employees were hired and today, according to the contractor, “Maintenance metrics have never been better and production has never been higher.”

Stories like this have been the extreme exception to the rule, say contractors, but fears of such horror stories are rising and haven’t been this prevalent since (you may repeat this aloud) the Great Depression.

What to farm out

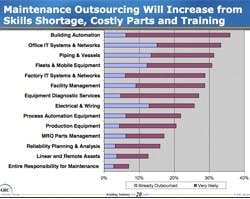

Figure 1. In 2006, plant managers said building automation showed the largest promise for potential outsourcing (Source: ARC).

Outsourcing takes many forms, from the automation OEM managing all of a company’s instruments and controls to specialized crafts contracted by the maintenance manager to the full-service firm taking over all services, people and systems, and reporting to the plant manager. What ties them together into a single category is “the existence of a contract, as opposed to calling an outside firm to come in and do some work on a per-job basis,” says Houghton Leroy, senior analyst with ARC Group (www.arcweb.com).

According to ARC’s research, plants typically devote 11% to 25% of their annual maintenance budget to contractors, a percentage Leroy expects to continue and perhaps increase as the economy worsens. The proportion that do full-department outsourcing is much smaller — single digits, he and others acknowledge — but he and outsourcing proponents indicate the practice will grow.

Figure 2. A new study by ARC (www.arcweb.com) shows cost reduction as fourth on the list of why companies contract for services.

ARC’s surveys indicate that the number of plants that already outsource services or are “very likely” to do so has more than doubled in recent years and now stands at 30% of manufacturing respondents. Building automation leads the list of outsourced activities in ARC’s research; at least 20% of manufacturers outsource in areas including production equipment, as well as electrical and wiring (Figure 1).

In ARC’s 2008 survey, 116 maintenance respondents in manufacturing industries indicated that “gaining access to specific skills” and “focusing employees on core needs” were the top two drivers (Figure 2).

Plant Services’ own survey of maintenance management professionals near the end of 2008 found that, in general, in-house expertise is preferred for critical or “state-of-the-art production equipment,” and is deemed more cost-effective for “mundane” tasks such as filter and coolant changes or hanging signs. But the consensus isn’t clear, as evidenced by the maintenance manager who said simple mechanical jobs and filter changes are the first items to outsource. Others are moving simple maintenance tasks over to the production department.

Of course, it’s common for expensive specialized or infrequent tasks to be contracted out, such as vibration and lubrication oil analysis and, as one manager says, electrical and welding work because that way, “We don’t have to issue hot work permits or provide appropriate PPE for arc flash hazards.”

Such specialized needs are often filled by OEMS like Schneider Electric’s Square D Services (www.squared.com), which

Figure 3. Access to specialists’ skills and equipment leads the list of reasons why companies contract for services.

manages customers’ electrical switchgear and related distribution assets (Figure 3). The company’s “sweet spot” is with customers “with more in-house expertise, who are at the forefront of doing maintenance,” says Hal Theobald, Square D product marketing manager. His reasoning is, “They’re going to be more likely to outsource because they still believe in doing maintenance right,” even as the economy forces staff reductions.

Benefits: The big picture

“Companies are being forced to reexamine how they’re doing things to gain more efficiency from their manufacturing assets,” says Jeff Owens, president, Advanced Technology Services (ATS, www.advancedtech.com), whose revenues have increased 20% to 25% annually during the past few years. ATS offers services ranging from filling a specific short-term need to taking over the full department, including asset management and information systems.

It’s important to evaluate outsourcing costs in terms of total plant performance because, Owens says, “A company might have been under-investing.” In such cases, maintenance department costs could rise, but the expenses are justified by benefits such as better management practices, lower scrap rates, higher productivity and lower total production costs … and better footing when the economy recovers.

For example, ATS has helped Textron’s E-Z-GO electric golf cart plant in Georgia reduce downtime, increase output and garner $570,000 in Six Sigma savings. Elsewhere, Eaton Aerospace, maker of electromechanical controls, has shortened production and delivery lead times with ATS while reducing critical machine downtime by as much as 30%. And J&L Fiber Services, which provides screening products to paper-makers, reduced downtime by as much as 600 hours per month while driving machine availability to 99.7%.

Overseas, Carter Holt Harvey’s Kinleath pulp and paper mill in Tokora, New Zealand, outsourced its entire maintenance operation in 2003 to ABB (www.abb.com). In the first year of operation, the company’s production operations broke 14 records, including a 10% increase in production volume and a 4% improvement in overall equipment effectiveness (OEE).

In addition to its global full-service maintenance business, ABB’s new Motor Performance Management business has been working with customers for roughly a year to maintain their motors and drives. The program has saved customers 15% to 30% on maintenance costs while boosting availability and reducing energy costs, says Dave Biros, business development director for ABB’s Reliability Services. He says energy savings can run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars annually for large plants, because motors can account for 60% to 70% of the plant’s electricity bills.

Biros says the typical company ABB targets for partial or full-service contracting has a “huge maintenance backlog due to any number of factors,” including poor management of the department, poor planning and scheduling, no CMMS or an underutilized CMMS, and “a misunderstanding of what requirements really are to improve maintenance.”

Is competence a concern?

When large organizations choose large partners to manage a large slice of the operation, even the outsource partner must outsource. For example, ABB’s full-service contract with a Big Three automaker’s plant in Brazil includes contracting for ancillary suppliers from glass, seat and tire plants to “the guys who cut the grass, wash the windows, run the cafeteria and water the plants,” Biros says. He adds that many of those activities are subcontracted to local and global suppliers, such as Johnson Controls for energy systems-related work.

There seem to be no limits on what can be outsourced. A high-level manager of a civilian firm handling operations and maintenance for a city-sized U.S. military base told us, “In my 28 years of experience, I have been associated, either as the customer or as the service provider, with outsourced operations and maintenance … including custodial work, security, operations of utilities, safety, maintenance of fire protection systems, design engineering, public affairs office, environment and hazardous waste, trash collection, street sweeping, port operations, handling of explosive ordnance, vehicle maintenance and even finance management.”

He says the most likely candidate for outsourcing “should always be the one that is most labor-intensive.” He starts with an analysis of manpower requirements based on the U.S. Department of Labor’s local wage determination scale, and applies historical man-hour requirements as recorded in the CMMS.

Contractor competence is occasionally questioned. Most maintenance managers report satisfaction with the skill levels of contractors, but one says, “It takes a while to get them on board and up to speed.” He blames maintenance cost overruns on “contractors’ lack of familiarity with nuclear power process delays.”

On the other hand, an outside contractor can “reach back,” says another respondent, into his firm’s organization to provide access to resources the in-house employee lacks.

Bonus: better information

Continuous improvement has long been a best practice, but an economic downturn can make it a mandatory key to survival. From total productive maintenance to Six Sigma, Lean and agile manufacturing, it’s impossible to succeed with continuous improvement initiatives without religious data entry.

When companies are muddling through lean times by slashing capital expenditures, maintenance of existing equipment takes on a more critical role. Ironically, now at the height of their importance, maintenance departments are seeing their resources vanish. Part of the solution is better scheduling, so activity tracking and PM logging become more important to the department’s survival in a down economy.

If in-house efforts fail because technicians slough off the timely logging of maintenance activities into the CMMS, a full-service contract could hold appeal. Contract workers live under a mandate to enter data for every job, and full-service contracts absolutely require it because they’re traditionally based on time and materials and increasingly include incentive-pay programs based on measured performance gains. In full-service contract agreements, the contractor “owns” the CMMS. It will either use the existing, installed system; recommend another (ABB prefers Maximo) or install its own if the plant consents (i.e. ATS’ eFactory Pro).

Experts estimate that as few as 20% of plants have a formal continuous improvement program, but 71% of our survey respondents had such a program in some state of implementation. These ranged from the maintenance manager embarking on a “a new adventure” he expects to be “hugely beneficial” for his company, to managers of multi-site programs like the one based on more than a dozen key performance indicators (KPIs) managed from an enterprise-wide SAP information backbone.

“We have targets for each facility and have a corporate staff of continuous improvement specialists who monitor the KPIs weekly and work with the plant managers and the [vice presidents] of the plants. Top criteria are maintenance labor cost per pound and M&R [parts and contractors] cost per pound. We also have KPIs that ensure labor and material costs are assigned to specific equipment. By comparing costs to the equipment level, we are able to benchmark costs for the same equipment across plants. We also have equipment grouped by functional location and can benchmark at that level also. Most of our plants don’t produce the same products, so the equipment and functional levels provide sufficient information to make decisions.”

Outsourced or not, failing to track maintenance metrics is “one of the biggest problems” departments face in the current economy, says ARC’s Leroy. “Whether you do it internally or externally, you still need to manage and monitor your assets.” Leading CMMS/EAM systems have steadily added contractor-management features and are good tools for managing service employees and partners.

If history repeats

“What we saw 15 years ago, and what we’re probably looking at it again today, is that as the economy slows down, our customers will see a slowdown in their orders,” says Ed Foster, vice president of Mundy Cos. (www.mundycos.com).

Looking back at past economic woes, Foster notes that some companies or plants will turn down production rates across the board, which minimizes asset wear and maintenance requirements. Some will take older, less-efficient equipment offline and consolidate production on their more modern equipment, which, again, reduces maintenance. The attendant manpower reduction can come from in-house or contract manpower, typically the latter first.

“Contractors are always the first resource you can cut back without experiencing bad relations with the local community,” Foster says. His firm provides maintenance services to roughly 75 companies, mostly in Sunbelt process plants, only a few of which are full-service partnerships. Taking the hits when the economy expands and contracts “is part of being a contractor,” he says.

Using the last recession as his guide, Foster foresees an upswing of loosening capital budgets to allow for replacement of older equipment with newer technology that's more efficient and reduces the manpower requirement per dollar spent. “The last time that happened, that spending mode lasted 10 years. And that’s probably what we'll see again. Whether that's two years or five years from now, I don’t know — my crystal ball isn’t that clear.”

Plant maintenance departments are, without question, facing a serious crisis. Despite layoffs that might alleviate a long-standing shortage of skilled workers in the field, the imperatives for new levels of efficiency might leave managers shorthanded even after an economic recovery, leading them to ask more outside contractors: Hey, buddy, can you spare a tech?

A full-service perspective

As many as 80% of maintenance departments are overstaffed, but don’t believe it “because they have big maintenance backlogs or other maintenance problems,” says Dave Biros, business development director for ABB’s Reliability Services (www.abb.com). “When we come in with better work processes, we can really take head count down,” he says, “but it's not just a head count game.”

In a full-service maintenance outsourcing agreement, the consensus seems to be that most — anywhere from 60% to 75% — of a plant’s employees are picked up by the contractor. Contractors report that transitioned workers historically retain the same level of compensation they had as an in-house employee. Whether the economy will produce a buyer’s market to change this, no one knows.

Biros and other contractors say that management often blames organized labor for their woes, and see circumventing the union as a major goal of outsourcing. Contractors say this attitude is myopic because it distracts them from considering their need for a more holistic solution.

Union labor can result in higher maintenance costs, such as when a company has to have a mechanic and a pipe-fitter and an electrician go on a service call as opposed to a cross-trained, non-union employee, says Jeff Owens, president, Advanced Technology Services (ATS, www.advancedtech.com). “But no one would do business with us if that’s all they looked at,” as opposed to the much broader view he and others take when partnering with a company.

Good communication and relations between in-house and contract workers is critical, Biros says, “because without an enthusiastic workforce, it's not going to work.” Plant Services survey respondents warn about culture clash, with one adding that educating workers about the financial aspects of a contracting decision at the plant resulted in a “good working relationship” with a “very happy union.”

Personnel who are dedicated to the maintenance field might benefit from being transitioned to a contract maintenance firm. As opposed to the “classic employment progression” that promotes non-maintenance workers vertically up the organization, maintenance career paths are "much more horizontal,” says Ed Foster, vice president, Mundy Cos. (www.mundycos.com). A maintenance manager — or a pipe-fitter — moves from company to company for advancement. Those who work for a firm dedicated to maintenance, it follows, might find greater job satisfaction at a time when their skills are up for grabs in the manufacturing world.

Bring ’em on

Operating on a smaller scale, but still outsourcing most of his department’s chores (not including management or CMMS administration), one Plant Services survey respondent, a maintenance manager who contracts out most of his department’s activities, shares these basic steps:

- First we identify areas that seem to have excess waste (non-value-added activity) that might lend themselves to outsourcing to reduce the waste.

- Second, we look in the marketplace to determine if there are firms or individuals that can provide the services needed.

- From there, we obtain quotations for the services and compare the outsourcing costs and in-house costs.

- If the costs of outsourcing are less than the costs of doing it in-house, there’s a reasonable possibility of outsourcing. Each case is unique and must be considered carefully because an error in judgment can have significant effects and can take significant time to recover. In today’s corporate atmosphere, it seems that outsourcing is easier to justify than adding a new associate, even though the mantra of most companies continues to be that “our employees are our most important asset.”

Note that departmental management and control of the CMMS/EAM system remain in-house, something that plants typically relinquish in a turnkey outsourcing partnership.

Risk and regulation

Plant Services survey respondents and other sources indicated that litigation and standards or regulations weren’t strong drivers of outsourcing versus in-house work, but there might be reason to reconsider the effect they can have on maintenance under any management scenario.

Square D’s raison d'être stems from its belief that maintenance of electrical distribution equipment historically hasn’t been a high priority. This is more critical than ever, as the economy ebbs and tightening capital budgets put a stronger emphasis on maintenance. “OSHA’s approach has been to adopt or follow whatever industry standards are in place. And during the last few years, they’ve been using NFPA 70E as their standard for electrical workplace safety,” Theobald says.

Arc flashes seriously injure or kill employees every day, which, in addition to the human devastation, can “easily” cost a company “$8 million to $10 million in direct and indirect costs,” says Joseph Weigel, product manager, Square D (www.squared.com), adding that legal settlements “almost always involve citations of deficiencies in the employer’s safety program as a causative factor.”

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 might someday be tested in court, and could become, like the NFPA standards, an issue that requires a more buttoned-down maintenance approach.

The post-Enron era “Sarbox” regulations establish accounting oversight of public companies and hold the CEO and CFO personally responsible for financial misstatements, under penalty of fines and imprisonment. The accounting rule relates to accounting for risk and exposing it to the public for the purposes of transparency. It’s not hard to imagine how a serious downtime event could affect financial position of the company.

"Imagine a conversation between a CEO and his staff, where the CEO is being asked, ‘sign this document.’ If it’s wrong, he goes to jail,” says Ralph Rio, research director, ARC (www.arcweb.com). What does the CEO do? Pass it around for the whole upper management team to sign.

Rio is “sensing that there's more attention being paid to equipment uptime, and understanding it, than there was prior to Sarbanes-Oxley” and a fear of improper documentation that can have “a trickle-down effect into maintenance management.”

Whether driven by Sarbox, NFPA 70E or any number of business drivers, risk in all its forms is driving a need for higher professionalism in the maintenance department, and might fuel the sense that maintenance is a noncore competence ripe for contracting.

The backlog roller-coaster

Hard economic times can produce a roller-coaster for maintenance backlog: the proportion of planned craft hours against available resources. In a down economy, backlog generally goes down, then up, then flatlines. In a manufacturing plant, for example, if incoming sales slow, idling production operations, maintenance crews might well find the time to zip though their backlogged jobs. But maintenance staff and budget cuts might follow any production turndown. Note the experience of this Plant Services research respondent at a plastics company:

“Currently, like many companies, our business is below “plan” and we do have more available time on the equipment to do maintenance work. The downside is that, as a percentage, more maintenance and fewer sales produce pressures to minimize maintenance activities. This isn’t a new phenomenon for us, but the longer we’re in a sales slump, the more pressure we see for layoff of our maintenance associates. Where our plant is situated, most of our turnover is caused by such soft business climates and attendant layoffs, rather than resignations. We are somewhat unique in this regard and blessed to be able to keep good people.”

Accordingly, some users report backlogs in various points on the trend cycle. Backlog is increasing for some managers who report budget cuts, layoffs and restrictions on overtime and a prohibition on outside contractors. “As usual in a down economy,” one says, “we now have the time and opportunity to make major repairs required, but no [money] for parts and contract labor. Cash is being reserved.” Staffs are being trimmed through attrition, another says, owing to “resistance to replace retiring maintenance workers in the next year or two.” Another says jobs are backing up because the growing list of refinery maintenance work “does not always understand that there is an economic downturn.”

Safety could be an issue, as evidenced by the “many” pockets of maintenance operations at one company that “have stopped planning … only performing what is necessary,” says another user, who reports shutting down all PMs and making only emergency repairs. Another response shows potential health and safety problems looming as “tasks deemed less important, even if they mean being out of compliance with OSHA, are being put on the back burner.”

Companies that remain financially healthy or otherwise retain their priorities as they head into a downturn might still find long-term strategies simmering on the back burner. One manager at a petrochemical plant says backlog has risen in response to staff cutbacks and PM processes that are less streamlined than they would be if the company sped up its failure mode and effects analysis and reliability-centered maintenance efforts.