In brief:

- And the first step down the road to improved wrench efficiency is a thorough understanding of how one’s time is currently spent.

- If you currently do not know where you are at, how can you possibly get to where you want to go?

- Reliability professionals who master the art of managing their time efficiently stand a greater chance of producing the asset improvement and cost reduction results that transform an organization into an industry leader.

Reliability professionals who master the art of managing their time efficiently stand a greater chance of producing the asset improvement and cost reduction results that transform an organization into an industry leader. Stephen Covey in his book “The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People” discussed the importance of living in Quadrant II, focusing on what is important and not urgent, rather than what is unimportant and urgent. But how are you supposed to do this, when the phone never stops ringing, the emails just keep coming, and there’s an endless line of people knocking on the door who just need five minutes of your time? While most companies with reliability programs measure craft “wrench” efficiency, how many reliability professionals measure their own wrench efficiency? Recognizing my own desire to improve both efficiency and effectiveness, I developed and used a time management tool to identify how I might improve my productivity. Identifying and eliminating Quadrant III (urgent and unimportant) activities allowed me to focus time and energy on Quadrant II activities; the structured and disciplined approached helped to increase my efficiency. As a byproduct, I was able to reduce my work hours and gain control of my personal and professional life, bringing it back into balance.

|

SMRP Conference Phil Beelendorf, CMRP, methods program coordinator at Roquette America, will present “Reliability Professionals — Improve Your Wrench Efficiency!” at the Society for Maintenance & Reliability Professionals Annual Conference in Indianapolis on Oct. 15 at 4 PM. The presentation will explain how to use this powerful tool to discover where you waste time. This knowledge and disciplined approach can help you to increase efficiency, keep commitments, and stay focused on the important tasks. Increasing productivity may also help to gain the healthy work/life balance we all strive for. Learn more about the SMRP Conference. |

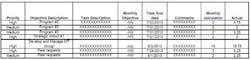

A journey of 1,000 miles starts with a single step. And the first step down the road to improved wrench efficiency is a thorough understanding of how one’s time is currently spent. This understanding cannot be gained without first measuring the amount of time spent on the various activities which comprise the work week. To accomplish this task, I developed an Excel spreadsheet in calendar form, listing the various objectives I was responsible for completing, along with the other activities I was involved in. The list included core activities such as the programs I managed, non-core activities such as mandatory training, answering emails, and other administrative tasks, and the key objectives listed on my performance management plan. The objectives on the performance management plan were treated as projects, whether they were strategic, managerial, or developmental in nature. During the initial three-month time-motion study, estimates on the amount of time spent on core and non-core activities were experiential guesses. The remaining hours were allocated to the various tasks that needed to be completed that month to meet the due dates listed on my performance management plan objectives. The desired goal of the initial time-motion study was twofold: to gain a better understanding of where my time was currently being spent and to develop the discipline necessary to work in a planned environment the majority of my time. I was embarking on a journey; I was heading down the road in search of the answer to the following question: “Was I in control of my time and work activities, or were they in control of me?”

It’s often beneficial to list an action plan for any activity or project, so clear improvement goals can be set from the observations made. The following action plan was developed for the three-month time-motion study.

- Estimate the amount of time spent on daily core and non-core activities. Record actual time spent on these activities to improve the accuracy of future estimates.

- Establish an hours-worked goal for the typical work week. For this study 50 hours/week was used. Determine number of work days available in the month. After subtracting the estimated hours spent on core and non-core activities, develop a list of planned task objectives you commit to working on, based on completion date and priority. Estimate tasks associated with each objective and provide a time estimate to complete all of the tasks planned for each objective that month. If there are too many hours scheduled, push low-priority tasks into the future; if you are under-scheduled, add additional tasks. For this study, the submitted plans started out 125-130% loaded. IE core, non-core, and planned activities equaled 125-130% of available hours. A target of 110% loading was established.

- Submit a plan to senior management at the beginning of each month outlining the planned objectives scheduled for the month in question. Record the time spent on each planned objective. Measure planned activity efficiency and wrench efficiency.

- Gain an understanding of the habits and practices that may limit efficiency. Develop the ability to work the majority of the day on planned activities. Know exactly which planned activities are scheduled each day before the work day starts.

- Identify hours spent on Quadrant III activities and record observations of ways to improve overall efficiency.

- Based on the observation made, develop an improvement plan to increase planned activity and wrench efficiencies.

For the purpose of this paper, planned activity efficiency is defined as “number of executed (actual) hours spent on project (planned) activities divided by total planned project hours.”

And wrench efficiency is defined as “number of scheduled core activity hours + number of executed (actual) hours spent on project (planned) activities divided by total available hours.”

The time-motion study can be created to suit any position or work situation. It can be used by people whose primary responsibilities are managing people, just as well as it can be used by people who spend the majority of their time managing tasks or projects. Each person should consider setting up the individual time categories to best describe their work week. The key is to accurately identify the work categories, accurately record the time spent on each category, and then identify those activities which waste time, and those which produce the greatest return on time invested. Once you understand how you spend your time and learn to recognize what the important (Quadrant II) and unimportant (Quadrant III) activities are, action plans can be developed and implemented to improve overall efficiency. Use these ground rules to improve the results of your study:

- The time-motion spreadsheet has two main tabs. The first is the data entry tab, in which the individual activity hours are recorded (Figure 1). The second is the monthly priorities tab, in which the monthly plan is developed (Figure 2).

- Individual tasks on the monthly priorities tab (task descriptions) are categorized under the various activities and objectives shown on the data entry tab. In this way they can be linked and rolled up into the time-motion study.

- As you think of tasks which need to be completed in a future month, insert a line on the monthly priorities tab along with time estimates and notes so planning the next month’s objectives becomes easy.

- To make recordkeeping practical, record activity blocks in 15-minute intervals. Try to avoid rounding up and attempt to keep the most accurate records as possible.

- Develop a category called “unaccounted for time” as a catch-all for any activities that take less than 15 minutes or for blocks of time where you completely lose focus because of interruptions, true emergencies, or when multiple activities come at you simultaneously. You might be surprised how often this occurs early in the study. You very well might lose track of time for 30 to 45 minutes quite easily when you become distracted or when things come at you from multiple directions.

- Try to come to work each day with a mental plan of what you hope to accomplish that day. As your discipline improves, you will find this gets easier and easier. Realize some days will bring emergencies and your best laid plans will go in the tank. Don’t get discouraged. Shake it off and come to work the next day with the attitude that things will be better.

- It only takes about 10 minutes each day to keep track of time. Keep a piece of paper sitting on the corner of your desk and record time blocks as you move from task to task. At the end of the day, record the information into the time-motion spreadsheet.

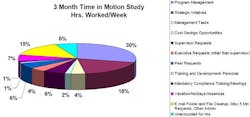

After three months of recordkeeping, I developed a clearer understanding of where my time was going. The results of the time-motion study, combining several objectives and activity categories into broader ones for graphical clarity, are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Breakdown of the first three months of the time-motion study.

Several interesting observations made during the study presented the cold hard facts, painting a revealing if not disturbing picture of inefficiencies I had subconsciously developed over time in my work habits.

- I was working on average 56.8 hours a week.

- 21% of my time was either unaccounted for, spent answering emails, or on other administrative tasks.

- I became too easily distracted. I noticed I had the habit of reading emails which popped up on my computer screen instead of staying focused on the task at hand.

- I did not always know what I planned to accomplish on any given day. Sure I had planned activities and meetings scheduled, but, quite often, I did not have a blueprint for the entire day clearly laid out in my mind before I went to work.

- I did not always organize my work in large enough blocks of time to create synergistic efficiency. Instead, at times, I randomly moved from task to task on the day I became aware of it. I did this quite often with the daily tasks associated with program management. An email came in; I looked at it and took care of it.

- 16% of my time was spent addressing supervisor, other senior manager and executive, and peer requests, most of which were not made with a time horizon that allowed me to schedule and plan them. Most of these requests had a short time horizon and were not planned or accounted for at the beginning of the month. If the requestor felt it needed to be done sooner than later, I was forced into deviating from my plan.

- I spent far too little time on personal development and growth. Even though I scheduled time each week for this activity, it was always the first thing to go when I needed to meet an approaching deadline. While this produced short-term results, it hindered long-term growth.

- Many times, I made a commitment without knowing whether I had given a realistic completion date. This forced me into working longer hours, delaying work on less critical projects to meet the deadline, or missing the deadline.

- I did not always know which activities produced the greatest return on time investment. I could measure payback, but since I didn't keep track of time spent, I did not know the return on my investment. This hurt my ability to focus my attention on the top priorities.

You’ve heard the idiom that necessity is the mother of all invention. Well, in my case, discovery was the mother of mine. I committed myself to re-invent the way I approached work in hopes of improving my efficiency. Out of the observations listed above and additional self discoveries made along the way, I embarked down the wrench efficiency road to self-improvement. I put together and executed the following action plan:

- I set a goal for myself to work 50 hours/week or less. I was committed to having more time and energy for the other important activities in my life.

- I identified the Quadrant III activities, which made up 21% of the time I spent at work, and resolved to reduce these wasted activities. Other than important emails, which I was expecting, I stopped reading my emails throughout the day, devoting time at the beginning and end of the day and over lunch to read and answer them.

- Emails responding to action items associated with the various programs I managed were not answered the day they were received. Instead, they were moved to a folder on Outlook. They were read and answered in scheduled time blocks to create synergistic efficiencies.

- I got better and better at anticipating peer and executive requests. The monthly objectives I sent to the senior managers included the commitments they needed to make for me to complete the stated objectives. In a way, I was asking them to share the responsibility for improving my wrench efficiency.

- Unless it was a true emergency, I reviewed existing planned workload before making commitments to new requests. I also asked for realistic “when do you need it” dates. When it did not seem possible to meet the date, I prioritized existing work and communicated to senior management and the original requestors which objectives I would need to defer to complete the new request. Reaching agreement and communicating the inability to meet a deadline as soon as it is recognized helps credibility and does less damage to your reputation as someone who is reliable and honors commitments than if you wait until the last moment to let someone know you will not meet your commitment.

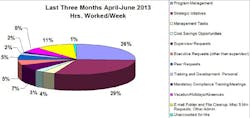

A commitment to the above stated goals, a little bit of hard work, and a disciplined approach combined to produce the results I desired. The time-motion study in Figure 4, with the same category combining for graphical clarity, illustrates improved performance in several key areas.

Figure 4. Breakdown of the most recent three months of the time-motion study (April-June 2013).

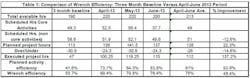

Planned activity and wrench efficiencies improved dramatically. Additionally, reductions in hours spent on non-core activities allowed an additional number of planned hours to be scheduled each month. The greatest improvement was seen in the number of executed project hours, which more than doubled (Table 1).

Table 1. The greatest improvement was seen in the number of executed project hours, which more than doubled.

Two of the most significant benefits realized from completing this exercise might, at first, appear intangible. But having a better understanding of the time it takes to complete tasks allows the reliability professional to better prioritize opportunities and set realistic completion dates for requests. As you get better at managing your workload and meeting deadlines, you will instill confidence and build trust among peers, senior management, and executive management. You, the reliability professional, will create the perception that you are reliable.

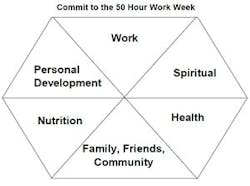

Figure 5. Nothing motivates like a constant reminder of what is truly important in life.

A side benefit was a reduction in hours worked, dipping from the aforementioned 56.8 hours/week down to 51.9. Not quite my 50 hour/week goal, but I’ll take it. Throughout the process, I kept this goal at the forefront of my thinking. I tend to be a conceptual thinker, so I find it helpful to create visual reminders to help me stay focused on my goals. The graph shown in Figure 5 hangs on the wall of my work and home offices as a constant reminder of what is truly important in my life.

Be careful not to confuse efficiency with effectiveness. As a Type A personality, I can get very passionate and zealous about squeezing the most out of every minute of the day. Remember the comment about reading my emails when I eat lunch. Relational effectiveness is important to success in any profession or activity. Unfortunately, it took me a long time to learn this. Care should be taken to retain the ability to change focus from tasks to people whenever interruptions occur during the workday. If you cannot change focus to actively listen to those who knock on your door asking for “five minutes” of your time, all the completed projects in the world will not erase the perception that you do not care about or have time for people.

In summary, the time-motion exercise and tools have helped me to understand how to work efficiently; stay focused on the task at hand, and prioritize work more effectively. A personal development coach I know has a favorite saying, “Where you look is where you will go.” Treat this activity like a roadmap between two points; the time-motion study reveals where you are at, the goals you set for yourself are your final destination, and the action plan you commit to completing is the highway which will ultimately get you there. In conclusion, consider this question: If you currently do not know where you are at, how can you possibly get to where you want to go?