Maintenance management: Stop the cost-cutting insanity!

In this article:

- Action 1: Understand that words matter

- Action 2: Learn from Moneyball

- Action 3: Observe by yourself

- Action 4: Facilitate a chalk circle workshop with your location lead team

- Action 5: Sustain an observation culture

Scenario 1: You come into work on Monday and the plant manager calls a special budget meeting to discuss the quarterly results for the business. The meeting begins with a process problem at a sister plant that impacts the financials for your business unit by $5 million. Each plant has been given a certain amount cuts to make in the next 60 days to ensure we make the quarter. Your plant has been allocated $500,000. You need to submit a plan by Friday and begin weekly calls tracking compliance with your controller.

Scenario 2: Your maintenance costs are increasing 5% per year and your overall equipment effectiveness (OEE) on your bottleneck production center is stagnant at 56%. Unplanned downtime is 33% of the gap to target OEE and results in a lot of daily drama, long hours, heroics, and organizational finger-pointing. Your planned-maintenance compliance is 60% because of the level of emergency work, which pulls resources to restore flow. You know how to fix the situation (execute on planned work, improve coverage of your predictive maintenance and reliability engineering to drive problem-solving), but cost-control mandates from top management on overtime, contractor spend, and headcount have you mired in mediocrity. Just last week your requests to backfill a planner and add a reliability engineer were turned down.

Joe Kuhn, CMRP, is a 32-year practitioner with Alcoa; is the owner of Lean Driven Reliability LLC; and hosts his own YouTube channel, Reliability Man. Joe can be contacted at [email protected].

Mark Keneipp, PE, CMRP is 35-year practitioner with Alcoa and is owner of Keneipp Consulting LLC. Mark can be contacted at [email protected].

Perhaps your plant has one or both of these situations (or others) dominating the culture. Most managers have a clear vision of where their organization needs to be and what systems need to be in place to get there. This vision remains part of the department’s plans, yet it’s never realized, given the very real obstacles and pressures that exist. This results in a feeling of powerlessness.

Cost-cutting fails every time, but it is the “go-to” tool in most organizations. Why? Cost cutting is simple; it’s easy to track; it provides immediate results; and it is a plan that can be provided to top management to demonstrate “bold leadership.”

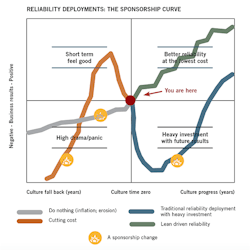

However, Figure 1 illustrates the impact of cost-cutting versus other reliability and maintenance improvement deployments. Notice how cost-cutting (the orange line) gets nearly immediate results, yet the returns fall off dramatically with time. Notice the impact on the culture: Progress actually reverts, often for years. “Waste elimination,” on the other hand, conjures up terms such as root-cause analysis, efficiency, wrench time, design improvements, consistency, performance optimization, predictability, and sustainability. Every tool in the maintenance and reliability toolbox at its core is designed to remove waste – we just are not selling it that way.

Stop the insanity! A revolution needs to take place within the reliability and maintenance community to change the dance. We must champion to organizational leaders an alternative that gives them great confidence in results that compete with the short-term infatuation we have with cost-cutting. This article proposes five specific actions we have found that can drive such a change.

Action 1: Understand that words matter

Beginning today, the reliability leader must become a champion of waste elimination. Relentlessly and consistently reframe all “cost-cutting” discussions to “waste elimination” – words matter. Be difficult. Challenge up and down the organization in every meeting, email, and conversation. Force everyone to the highest standards by driving sustainable changes unlocked by a waste-elimination mindset.

Waste-elimination efforts prove you are using the resources you have to the maximum. Everyone wants more people – more planners, supervisors, engineers, and craftspersons. The leader must establish credibility through results with current resources to warrant investment. The reality is the plant manager gets 10 new investment ideas a day. Most are dismissed, and those that are accepted have a poor track record of delivering on hypothesized outcomes.

We in reliability must stand out from this pack. We do this with one word – credibility. Some examples:

- If you are at 15% wrench time, asking for more people is irresponsible. Cut the waste first to establish credibility, and then ask for resources. Add a job-kitter/stager role (within current headcount) to get wrench time to 30% (or some plateau), and then go to management with the savings and your plan to go to another level, where you invest only a portion of the dollars already saved.

- If you are short on planners, elevate a craftsman to a planner for 120 days. Document the gains in wrench time or OEE and then ask for reinvestment of a portion of the savings by hiring a full-time professional planner.

- If you need a reliability engineer, reorganize for 90 days to conduct an experiment of having a dedicated reliability engineer (by the way, part-time reliability engineers are an illusion). Document impact and approach leadership with these facts. If the answer is still no, consider reorganizing and contracting out low-cost engineering tasks. Document the delta in costs for a new sales pitch in six months.

You need to create a communication plan to keep waste-elimination successes front of mind for everyone – both sponsors and the organization – and to establish credibility before asking for any additional resources. Examples include: a weekly email single-point lesson of a condition monitoring find and the impact; a monthly presentation to the lead team by the condition monitoring technicians about successes, failures, and help needed; and communications about improvements in wrench time resulting from job kitting/staging and PM compliance.

Assuming others know your results is a mistake. Communication will serve as evidence that the waste elimination plan is working.

Action 2: Learn from Moneyball

“Moneyball” is a 2011 movie about the 2002 Oakland A’s Major League Baseball team. In the movie, the general manager, Billy Beane (played by Brad Pitt), is challenged to build a team to compete with the New York Yankees on a $40 million/year budget when the Yankees were spending $120 million.

Beane stumbles upon Peter Brand (played by Jonah Hill), who has a revolutionary method for evaluating players. Brand values on-base-percentage and statistics over player traits and perceived weaknesses. With this method, the team spotted greatly undervalued players and secured them for 10%–30% of their true output value. The A’s did not win the World Series that year, but they did break the American League number of consecutive wins (20) and achieved the same number of season wins as the Yankees.

So, what does this have to do with reliability and maintenance? Beane was mired in doing things the traditional way but kept “losing the last game” (i.e., not winning the World Series). He found new best practices through Brand, but the cultural inertia was great – over 100 years of tradition. The personal attacks, challenges, setbacks, loneliness, failures, and risk endured by Billy and Peter were enormous. The media were relentless.

We have found the challenge of changing the culture in our organizations very similar and the film motivational and instructive. How do we affect culture? Answer: one experience at a time. Fundamental change takes time. Just like the A’s started racking up wins, the practitioner must chalk up wins. We are competing against “cost-cutting,” so we propose that we need measurable signs of progress in under 90 days, with some successes to provide reason for hope in 30 days.

We challenge you to relate to either Billy or Peter and to remember the line uttered by the owner of the Red Sox at the end of the movie: “The first guy through the wall always gets bloody; people feel threatened; their livelihoods are at stake. The culture will go batty; but they are dinosaurs.”

After all, every major league team now utilizes Peter’s approach to valuing players.

Action 3: Observe by yourself

Read about the seven forms of waste. Understand the chalk circle of observation. These are easy to learn more about online.

Next, go out and observe a job for four hours. The start of the shift and the end of the shift will be the most fruitful for observation. Mornings have all of the coordination and parts issues, and end-of-shift reveals issues with duration and resource management. Don’t give up after 30 minutes or two hours; stick it out. Look for waste over 10 minutes – don’t bother with seconds. Ensure you are counting working resources and the value of work being completed.

Greet the crew and inform them you are looking for ways to remove barriers to their success, such as the use of wrong parts or poor coordination. The crew will quickly become your partner. Individuals became craftspersons because they like to fix things and have them run well. Delays frustrate them just as much as you. Do not influence the decision-making or work – be a fly on the wall.

After you collect the data, ask yourself:

- What was the wrench time?

- What simple issues affected wrench time, e.g., coordination, parts availability, crew pulled for emergency work?

- Was the action taken the best solution? Was the action taken based on failure mode or fear?

- Was condition monitoring technology used properly?

- Is there an engineering solution to prevent recurrence or to change MTBF? Why is the engineer not working on the solution? Busy on other priorities or pulled into restoring flow? Do you have a reliability engineer in name only?

- Would you pay for the labor hours you observed on a home repair by a service provider?

When we have facilitated such observations, we have found the biggest challenge is to get the observer to not write off the “shockingly inefficient” observation as an anomaly. Consequently, we have evolved the training to include a pledge by observers to swear, “Today is not the worst day ever and tomorrow will not be the second-worst – both are reality and I choose to own it.” Expect to be amazed at how simple things result in the vast majority of the waste (this is truly great news).

Action 4: Facilitate a chalk circle workshop with your location lead team

This is a bold step, and only the confident leader will take this action. This is a typical plan for a large location; feel free to adapt to your situation:

- Pre-workshop, train a coach for each lead team member involved (be sure to include your controller, for he or she will be keeping score of actions versus cost-cutting).

- Lead team and coaches block out days for workshop. (We recommend a half-day on Monday; full days Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday; and a half-day on Friday).

- Monday will be for training on how to observe work, understanding waste, the meaning of wrench time, preventive maintenance, predictive maintenance, MTBF, OEE, and reliability engineering.

- Tuesday through Thursday will be observation. Each lead team member and coach will be assigned a maintenance job to observe. Cover as many areas of the plant as possible. Begin with the morning toolbox talk and end at shift change. Lead team members and coaches are to reconvene in a conference room for a debrief. Record observations and common themes, both positive and negative.

- In Wednesday and Thursday afternoon debriefs, spend 10 minutes looking at the previous day’s common themes. Do they repeat or are they new?

- On Friday, prioritize the common themes by impact, timeline, and ease of implementation. As a team, craft 30-, 60- and 90-day action plans. Focus most on getting quick, meaningful waste-elimination wins that can compete with cost-cutting. Detail how you intend to measure success with cost and key performance indicators (KPIs).

Congratulations! You just created an experience for the lead team that will alter their thinking for the rest of their career. You provided a simple, meaningful, and sustainable alternative to “cutting costs” that will energize the organization and, of most importance, sponsors.

From these early wins you will establish credibility, and from credibility you can ask for additional resources to further elevate performance.

Action 5: Sustain an observation culture

Now that you are a believer in chalk circle observations, what can you do to sustain it? Pick one or all of these five and add some of your own. Seeing reality is empowering and engaging.

- Seek sponsorship to block out on everyone’s electronic calendar from noon to 4 p.m. on Wednesday for observation of standard work time. Ensure the lead team members are role models.

- Set an expectation for all personnel to audit standard work of one job per month. Minimum time is 4 hours per observation.

- Create training on how to observe standard work. Require leaders/students to certify as proficient by demonstrating the skill to the coach five times on an A3 by year end.

- Do not approve funds, resources, or headcount replacements/adds without chalk-circle data.

- Establish a “go and see” culture after all major equipment or process deviations.

Results

While we cannot discuss plant specifics, in general we have seen a 10% cut in waste from repair and maintenance budgets in year one (some more and some less depending on current state). Some teams need to reinvest a portion of this savings due to past cost-cutting decisions. What is critical to note is that you do not need to invest huge dollars up front to begin the waste elimination journey. Observation is the key you need to unlock your adventure.

In conclusion, we believe manufacturing is in the midst of an epidemic of failure in how we manage equipment – most in leadership are not even aware of the disease. The result is higher costs, lower production, excessive drama, frustration, helplessness, attrition, and long work hours. The maintenance and reliability community must lead the charge away from cost-cutting and play the infinite game.

It’s just five actions, but together they represent “one giant leap” for your reliability journey.